Let's start by taking a step-by-step look at the basic OpenID protocol to see how the phishing attack works. (Click on the diagrams to see them on a more readable scale.)

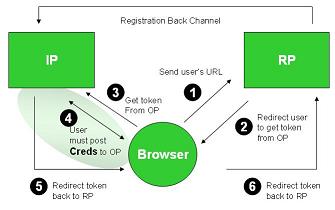

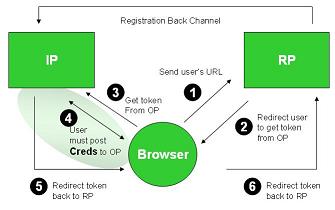

The system consists of three parties – the relying party (or RP) which wants an ID in order to provide services to the user; the user – running a browser; and the Identity Provider (OpenID affectionados call it an OP – presumably because the phrase Open Identity Identity Provider smacks of the Department of Redundancy Department. None the less I'll stick with the term IP since I want to discuss this in a broader context).

OpenID can employ a few possible messages and patterns, but I'll just deal with the one which is of concern to me. An interaction starts with the user telling the RP what her URL is (1). The RP consults the URL content to determine where the user's IP is located (not shown). Then it redirects the user to her IP to pick up an authentication token, as shown in (2) and (3). To do the authentication, the IP has to be sure that it's the user who is making the request. So it presents her with an authentication screen, typically asking for a username and password in (4). If they are entered correctly, the IP mints a token to send to the RP as shown in (5) and (6). If the IP and RP already know each other, this is the end of the authentication part of the protocol. If not, the back channel is used as well.

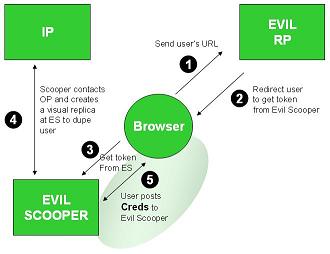

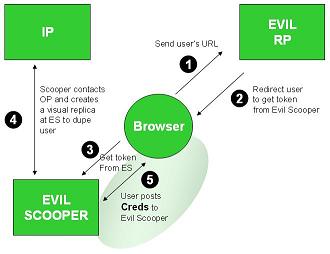

The attack works as shown in the next diagram. The user unwittingly goes to an evil site (through conventional phishing or even by following a search engine). The user sends the evil RP her URL (1) and it consults the URL's content to determine the location of her IP (not shown). But instead of redirecting the user to the legitimate IP, it redirects her to the Evil Scooper site as shown in (2) an (3). The Evil Scooper contacts the legitimate IP and pulls down an exact replica of its login experience (it can even simply become a “man in the middle”) as shown in (4). Convinced she is talking to her IP, the user posts her credentials (username and password) which can now be used by the Evil Scooper to get tokens from the legitimate IP. These tokens can then be used to gain access to any legitimate RP (not shown – too gory).

The problem here is that redirection to the home site is under the control of the evil party, and the user gives that party enough information to sink her. Further, the whole process can be fully automated.

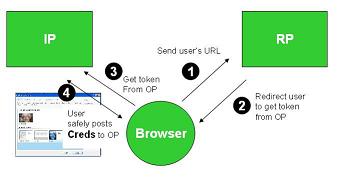

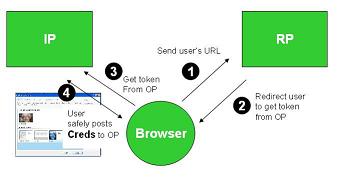

We can eliminate this attack if the user employs Cardspace (or some other identity selector) to log in to the Identity Provider. One way to do this is through use of a self-issued card. Let's look at what this does to the attacker.

Everything looks the same until step (4), where the user would normally enter her username and password. With self-issued cards, username and password aren't used and can't be revealed no matter how much the user is tricked. There is nothing to steal. The central “honeypot credentials” cannot be pried out of the user. The system employs public key cryptography and generates different keys for every site the user visits. So an Evil Scooper can scoop as much as it wants but nothing of value will be revealed to it.

I'll point out that this is a lot stronger as a solution than just configuring a web browser to know the IP's address. I won't go into the many potential attacks on the web browser, although I wish people would start thinking about those, too. What I am saying is the solution I am proposing benefits from cryptogrphy, and that is a good thing, not a bad thing.

There are other advantages as well. Not the least of these is that the user comes to see authentication as being a consistent experience whether going to an OpenID identity provider or to an identity provider using some other technology.

So is this just like saying, “you can fix OpenID if you replace it with Cardspace”? Absolutely not. In this proposal, the relying parties continue to use OpenID in its current form, so we have a very nice lightweight solution. Meanwhile Cardspace is used at the identity provider to keep credentials from being stolen. So the best aspects of OpenID are retained.

How hard would it be for OpenID producers to go in this direction?

Trivial. OpenID software providers would just have to hook support for self-issued cards into their “OP” authentication. More and more software is coming out that will make this easy, and if anyone has trouble just let me know.

Clearly not everyone will use Infocards on day one. But if OpenID embraces the alternative I am proposing, people who want to use selectors will have the option to protect themselves. It will give those of us really concerned about phishing and security the opportunity to work with people so they can understand the benefits of Information Cards – especially when they want, as they inevitably will, to start protecting things of greater value.

So my ask is simple. Build Infocard compatibility into OpenID identity providers. This would help promote Infocards on the one hand, and result in enhanced safety for OpenID on the other. How can that be anything other than a WIN/WIN? I know there are already a number of people in the milieux who want to do this.

I think it would really help and is eminently doable.

This said, I have another proposal as well. I'll get to it over then next few days.

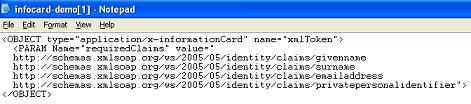

In the case described by Pat, the site really does use a “registration” model like the one from BestBuy shown here.

In the case described by Pat, the site really does use a “registration” model like the one from BestBuy shown here.