Kim Komando has a great piece at USA Today where she explains geotagging through the experiences of two women who also happened to be using the foursquare location service. This article is one of the first of what I expect will become a torrent as the media learns the implications of geolocation:

Sylvia was dining out with a friend. The restaurant manager interrupted her dinner to tell her she had a phone call. It was from a complete stranger who tracked her online. He had described her to the manager.

Louise was at a bar with colleagues. A stranger began talking to her. He knew a lot about her personal interests. Then, he pulled out his phone and showed her a photo. It was a picture of Louise that he found online.

Both of these stories are true. And they're very unnerving. There is also a common thread. The women were tracked by something known as “geotagging.”

Geotagging adds GPS coordinates to your online posts or photos. You may be exposing this information without even knowing it. Geotagging is particularly popular with photos; many smartphones automatically geotag photos.

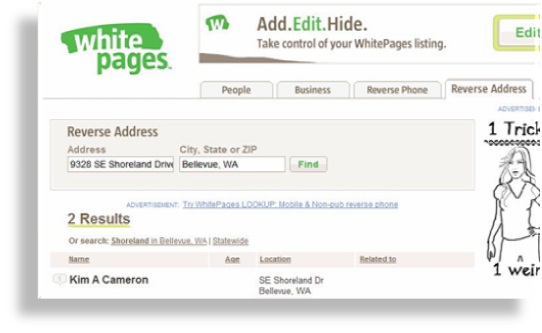

Photos can be plotted on a map for easy organization and viewing. But if you post photos online, and you could reveal your home address or child's school. You've given a criminal a treasure map.

Layers of information

A geotagged photo is the most obvious threat to your privacy and safety. But, in Louise's and Sylvia's cases, there was more going on. Both used the location-based social-networking service Foursquare.

Location-based social-networking services are designed to help you meet up with family and friends. When you're out and about, you check in with the site. At the coffee shop? Check in so friends nearby can find you.

Unless you have a stalker, these services aren't particularly dangerous on their own. You need to think about the layers of information you leave online. As you use more services, it's easier for criminals to track you.

Let's say you post a photo of your new house to a photo site. The photo is geotagged. You've linked your photo account to Facebook. And you use Foursquare or Twitter on the go; updates are sent to your Facebook account.

One night you go to the movies. You send a tweet as you wait in line. When you get home, you discover you've been robbed. The burglar used your photo to find your address. He learned more about you on Facebook. Your tweet tipped him off to your location.

Thanks to a movie site, he knew exactly how long the movie ran. He scoped out your house and neighborhood on Google Street View. He devised a plan to get in and out fast and undetected.

Protecting yourself

If you use these services, protect yourself. Use a little common sense. First, don't geotag photos of your house or your children. In fact, it's best to disable geotagging until you specifically need it.

On the iPhone 4, tap Settings, then General, and then Location Services. You can select which applications can access GPS data. These options aren't available in older iPhone software, so tap Settings, then General, then Reset. Tap Reset Location Warnings. You'll be prompted if an application wants to access GPS data. You can then disallow it.

In Android, start the Camera app and open the menu at the left. Go into the settings and turn off geotagging or location storage, depending on which version of Android is on your phone. On a BlackBerry, click the Camera icon. Press the Menu button and select Options. Set the Geotagging option to Disabled. Save your settings.

You can also use an EXIF editor to remove location information from photos. EXIF data is information about a photo embedded in the file. Visit www.komando.com/news for free EXIF editors.

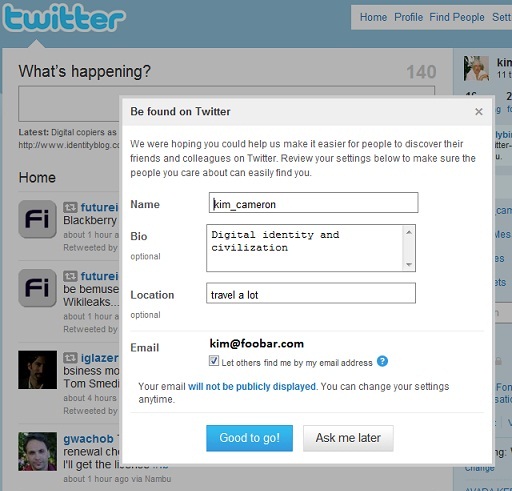

Don't check in on Foursquare or similar sites from home. And make sure your Twitter program is not including GPS coordinates in your tweets.

For many people, Facebook ties everything together. Reconsider linking other accounts to Facebook. Pay close attention to your privacy settings. Only trusted friends should know when you are or aren't at home. Finally, if you have contacts you don't fully trust, it's time to do a purge.

[Kim Komando hosts the nation's largest talk radio show about computers and the Internet. To get the podcast or find the station nearest you, visit www.komando.com. To subscribe to Kim's free e-mail newsletters, sign up at www.komando.com too. Contact her at C1Tech@gannett.com. ]

It is well worth reading Foursquare's privacy policy – which is well thought out and makes Foursquare a paragon of virtue when compared to the contract with the devil you sign when you install iTunes, for example. I'll explore this more going forward.