Todd Bishop at TechFlash published a comprehensive story this week on device fingerprints and location services:

Kim Cameron is an expert in digital identity and privacy, so when his iPhone recently prompted him to read and accept Apple's revised terms and conditions before downloading a new app, he was perhaps more inclined than the rest of us to read the entire privacy policy — all 45 pages of tiny text on his mobile screen.

It's important to note that apart from writing his own blog on identity issues — where he told this story — Cameron is Microsoft's chief identity architect and one of its distinguished engineers. So he's not a disinterested industry observer in the broader sense. But he does have extensive expertise.

And he is publicly acknowledging his use of an iPhone, after all, which should earn him at least a few points for neutrality…

At this point I'll butt in and editorialize a little. I'd like to amplify on Todd's point for the benefit of readers who don't know me very well: I'm not critical of Street View WiFi because I am anti-Google. I'm not against anyone who does good technology. My critique stems from my work as a computer scientist specializing in identity, not as a person playing a role in a particular company. In short, Google's Street View WiFi is bad technology, and if the company persists in it, it will be one of the identity catastrophes of our time.

When I figured out the Laws of Identity and understood that Microsoft had broken them, I was just as hard on Microsoft as I am on Google today. In fact, someone recently pointed out the following reference in Wikipedia's article on Microsoft's Passport:

“A prominent critic was Kim Cameron, the author of the Laws of Identity, who questioned Microsoft Passport in its violations of those laws. He has since become Microsoft's Chief Identity Architect and helped address those violations in the design of the Windows Live ID identity meta-system. As a consequence, Windows Live ID is not positioned as the single sign-on service for all web commerce, but as one choice of many among identity systems.”

I hope this has earned me some right to comment on the current abuse of personal device identifiers by Google and Apple – which, if their FAQs and privacy policies represent what is actually going on, is at least as significant as the problems I discussed long ago with Passport.

But back to Todd:

At any rate, as Cameron explained on his IdentityBlog over the weekend, his epic mobile reading adventure uncovered something troubling on Page 37 of Apple's revised privacy policy, under the heading of “Collection and Use of Non-Personal Information.” Here's an excerpt from Apple's policy, Cameron's emphasis in bold.

We also collect non-personal information — data in a form that does not permit direct association with any specific individual. We may collect, use, transfer, and disclose non-personal information for any purpose. The following are some examples of non-personal information that we collect and how we may use it:

We may collect information such as occupation, language, zip code, area code, unique device identifier, location, and the time zone where an Apple product is used so that we can better understand customer behavior and improve our products, services, and advertising.

Here's what Cameron had to say about that.

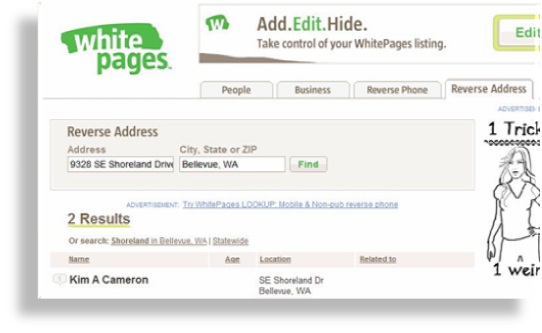

Maintaining that a personal device fingerprint has “no direct association with any specific individual” is unbelievably specious in 2010 — and even more ludicrous than it used to be now that Google and others have collected the information to build giant centralized databases linking phone MAC addresses to house addresses. And — big surprise — my iPhone, at least, came bundled with Google’s location service.

The irony here is a bit fantastic. I was, after all, using an “iPhone”. I assume Apple’s lawyers are aware there is an ‘I’ in the word “iPhone”. We’re not talking here about a piece of shared communal property that might be picked up by anyone in the village. An iPhone is carried around by its owner. If a link is established between the owner’s natural identity and the device (as Google’s databases have done), its “unique device identifier” becomes a digital fingerprint for the person using it.

MAC in this context refers to Media Access Control addresses associated with specific devices, one type of data that Google has acknowledged collecting. However, in a response to an Atlantic magazine piece that quoted an earlier Cameron blog post, Google says that it hasn't gone as far Cameron is suggesting. The company says it has collected only the MAC addresses of WiFi routers, not of laptops or phones.

The distinction is important because it speaks to how far the companies could go in linking together a specific device with a specific person in a particular location.

Google's FAQ, for the record, says its location-based services (such as Google Maps for Mobile) figure out the location of a device when that device “sends a request to the Google location server with a list of MAC addresses which are currently visible to the device” — not distinguishing between MAC addresses from phones or computers and those from wireless routers.

Here's what Cameron said when I asked about that topic via email.

I have suggested that the author ask Google if it will therefore correct its FAQ, since the portion of the FAQ on “how the system works” continues to say it behaves in the way I described. If Google does correct its FAQ then it will be likely that data protection authorities ask Google to demonstrate that its shipped software behaving in the way described in the correction.

I would of course feel better about things if Google’s FAQ is changed to say something like, “The user’s device sends a request to the Google location server with the list of MAC addresses found in Beacon Frames announcing a Network Access Point SSID and excluding the addresses of end user devices.”

However, I would still worry that the commercially irresistible feature of tracking end user devices could be turned on at any second by Google or others. Is that to be prevented? If so, how?

So a statement from Google that its FAQ was incorrect would be good news – and I would welcome it – but not the end of the problem for the industry as a whole.

The privacy statement for Microsoft's Location Finder service, for the record, is more specific in saying that the service uses MAC addresses from wireless access points, making no reference to those from individual devices.

In any event, the basic question about Apple is whether its new privacy policy is ultimately correct in saying that the company is only collecting “data in a form that does not permit direct association with any specific individual” — if that data includes such information as the phone's unique device identifier and location.

Cameron isn't the only one raising questions.

The Consumerist blog picked up on this issue last week, citing a separate portion of the revised privacy policy that says Apple and its partners and licensees “may collect, use, and share precise location data, including the real-time geographic location of your Apple computer or device.” The policy adds, “This location data is collected anonymously in a form that does not personally identify you and is used by Apple and our partners and licensees to provide and improve location-based products and services.”

The Consumerist called the language “creepy” and said it didn't find Apple's assurances about the lack of personal identification particularly comforting. Cameron, in a follow-up post, agreed with that sentiment.

SF Weekly and the Hypebot music technology blog also noted the new location-tracking language, and the fact that users must agree to the new privacy policy if they want to use the service.

“Though Apple states that the data is anonymous and does not enable the personal identification of users, they are left with little choice but to agree if they want to continue buying from iTunes,” Hypebot wrote.

We've left messages with Apple and Google to comment on any of this, and we'll update this post depending on the response.

And for the record, there is an option to email the Apple privacy policy from the phone to a computer for reading, and it's also available here, so you don't necessarily need to duplicate Cameron's feat by reading it all on your phone.

Regular readers will have come across (or participated in shaping) some of my work over the last year as I looked at the different ways that device identity and personal identity collide in mobile location technology.

Regular readers will have come across (or participated in shaping) some of my work over the last year as I looked at the different ways that device identity and personal identity collide in mobile location technology.

But then – the coup de grace. The privacy policy to which Apple redirects you is… are you ready… the same one we came across a few days ago at the App Store! So once again you need to get to the equivalent of page 37 of 45 to read:

But then – the coup de grace. The privacy policy to which Apple redirects you is… are you ready… the same one we came across a few days ago at the App Store! So once again you need to get to the equivalent of page 37 of 45 to read: