I always want my blog to be about ideas, not the specific products I work on.

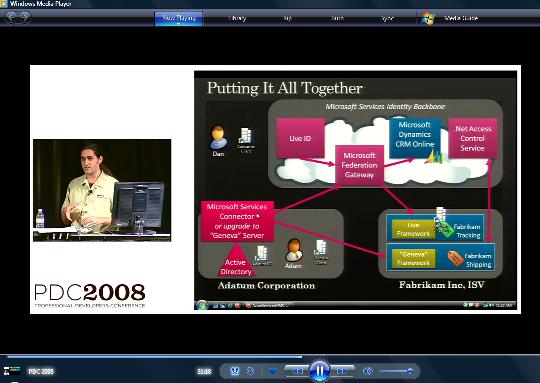

But I thought it might be useful to make a bit of an exception in terms of sharing the announcements I made this week at the Microsoft Professional Developers Conference in Los Angeles. I'm hoping this might help others in the industry understand exactly what we at Microsoft been able to accomplish around identity, what's left to do, and where we think we're going.

A number of people have told me that one of the conclusions they drew from the presentation is that when it comes to identity, big, synergistic, cross-industry things are happening. I liked that.

Not random things, not proprietary things, not divisive things. But initiatives that further our collaboration, open standards, user choice and control and the “identity metasystem” many of us believe in so strongly, even if we call it by different names.

I thought it might help, in particular, to share the conversation we are having with our developers. This set of posts is intended as a bit of a look behind the curtain – or rather, as pulling back the curtain to show there is no curtain, if you will. My presentation, which is on video here, went like this…

The first lines of every application

Whether you are creating serious Internet banking systems, hip new social applications, multi-party games or business applications for enterprise and government, you need to know something about the person using your application. We call this identity.

Whether you are creating serious Internet banking systems, hip new social applications, multi-party games or business applications for enterprise and government, you need to know something about the person using your application. We call this identity.

There is no other way to shape your app to the needs of your users, or to know how to hook people up to the resources they own or can share.

I want to be clear. Knowing “something” doesn't mean knowing “everything”. We want to keep from spewing personal information all over the Internet. It means knowing what’s needed to provide the experience you are trying to create.

This might sometimes include someone’s name. Or knowing they are really the person with a certain bank account.

Or it might just involve knowing that someone is in a certain role. Or in a certain age bracket.

It also might simply be a question of remembering that some user prefers Britney Spears to New Kids on the Block or Eminem.

Identity Turbulence

But getting identity information is one of the messiest aspects of application development. People are up to their necks in passwords. They use many different mechanisms to establish identity, and its getting worse.

One of my good friends at Microsoft is in charge of the identity aspects of one of our flagship apps. Let’s call him Joe .

He started years ago by building in support for usernames and passwords. He was supposed to finish up within a few weeks, but soon found he needed a second project to build in better password reset and account management.

This soon worked pretty well, but when presented to customers, no one would deploy in large numbers unless he added a help desk component – so he did.

Then as Active Directory started gaining critical mass, he needed to set up a project to integrate with Active Directory. When that was finished, the large sites wanted to use AD with multiple forests, and that involved a complete rewrite…

Next, people wanted to use the app outside the firewall, so he needed to add One Time Password (OTP) support. Supporters of Smart Cards were adamant that if OTP was supported, smartcards should work too.

Joe was just pretty much ready to return to his “core work” when he was asked to support SAML. He hadn't even finished his initial investigation of this when people started asking for OpenID support too. Plus he needed to integrate with another software product by a different vendor – who used a completely different and proprietary approach to identity.

As he was looking at all this he was hit by phishing attacks. That brought about a whole new round of security reviews – one for every one of the projects just discussed.

Now Joe has realized that his application has to be easily hostable in the cloud as well as work on-premise. And it needs to support delegation so it can access other services on behalf of his users…

So you’ll understand that he really wants and needs a better way. He wants to focus on the core values of his app, not the changing trends in identity.

Claims-based Access

As we understood more about these problems, and the hardships they were causing developers, we started work on a way to insulate the application from all these issues.

Our goal? You – the developer – would write the application once and be done, yet it would support all the identity requirements customers have as they host it in different environments.

This was the same kind of problem we had in spades in the early days of computing. Back then, you needed to write separate code for each type of disk drive you wanted to support. There was no end to it. If you didn’t support the new drives you’d lose part of your market. So we needed the idea of a logical disk that was always the same.

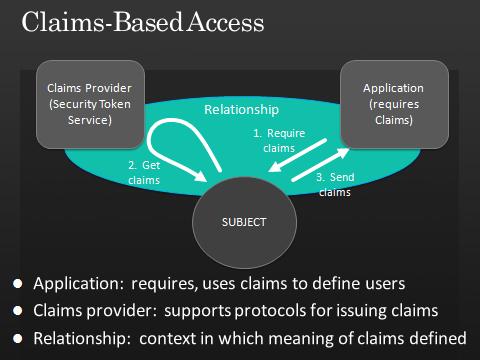

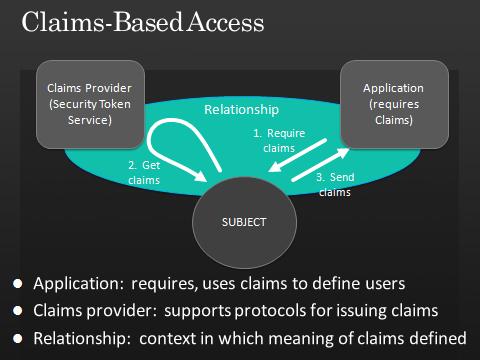

We can now do the same thing around identity. We use what we call the Claims Based model.

A claim is a statement by one subject about another subject. Examples: someone's email address, age, employer, roles, custumer number, permission to access something. There are no constraints on the semantics of a claim.

The model starts from the needs of the application: you write your application on the assumption you can get whatever claims you need.

Then there is a standards-based architecture for getting you those claims. We call it the Identity Metasystem – meaning a system of identity systems.

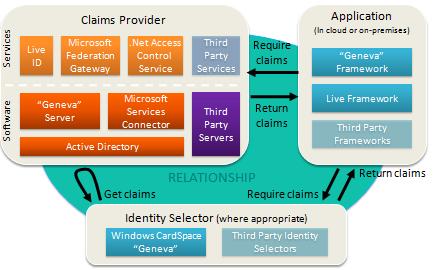

Here’s how the architecture works. As I said, the application is in control. It specifies the kinds of claims it requires. The claims providers support protocols for issuing claims. You can also pop in claims providers that translate from one claim to another – we call this claims transformers. That makes the system very flexible and open.

The technical name for a claims provider is a “Security Token Service”. You’ll see the abbreviation STS on upcoming slides.

The important thing here is that all existing identity mechanisms can be represented through claims and participate in the metasystem. As an app developer, you just deal with claims. But you get support for all permutations and combinations without getting your hands dirty or even thinking about it.

I say “all” to emphasize something – the open nature of this system. It accepts and produces identities from and for every type of platform and technology – no walled gardens.

You can choose to get your identity from anywhere you wish. You can choose any framework to build your app. You can choose to use any client or browser.

What's involved for the developer?

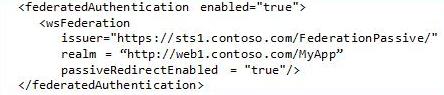

Let me give you an example. I'll peek ahead and show you how the claims-based model is used in the Geneva Framework – new capabilities within .NET. Other frameworks would have similar capabilities, though we think our approach is especially programmer-friendly.

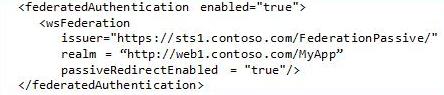

Basically, to answer the “Who are you?” question, you write your app as per normal, and simply add this extra configuration to you app.config file:

(There are a couple of more cut-and-paste lines needed, to make sure some modules are included, but otherwise that’s it.)

Now, when a user hits your app, if they haven't been authenticated yet, they will get automatically redirected to the claims provider at https://sts1.contoso.com/FederationPassive to pick up their claims. The claims provider will get your user to authenticate, and if all goes well, will redirect her back to your application with her identity set, and any necessary claims available to your program. In other words, with zero effort on your part, no unauthenticated user will ever hit your app. Yet you are completely free to point your app at any claims provider on any platform made by any vendor and located anywhere on the Internet.

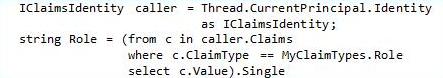

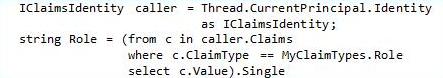

To drill into the actual claim values, you use a technique like this:

You’ll see the Thread has a Current Principal, and the Principal has an Identity, so you get a Claims Identity interface as shown, then cycle through the claims or pull out the one you need. In this case, it is the claim with the type of “role” – in the the enum MyClaimTypes.Role…

If you are an application developer, we've already come to the big takeaway of this presentation. You can get up and go home now. Everything else I’m going to show you is just to give you a deeper understanding of all the many use cases and scenarios that can be supported through these mechanisms.

Again, the claims shown in this example are implemented through well accepted industry standards. The same code works with claims that come from anywhere, any platform, any vendor, any operating system, any cloud provider.

Solving problems with claims

{In the next segment, I'll share the ideas I presented to my developer audience about how they could use claims to solve concrete problems.}

We have another announcement that really drives home the flexibility of claims.

We have another announcement that really drives home the flexibility of claims.

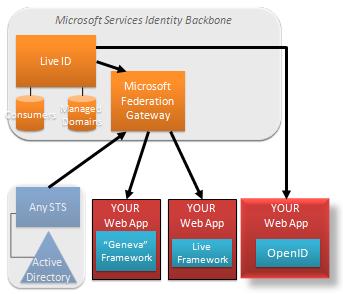

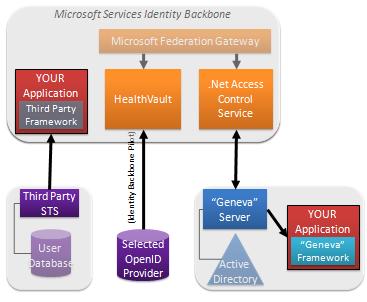

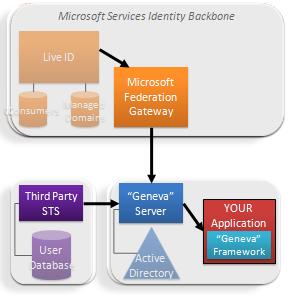

Microsoft also operates one of the largest Claims Providers in the world – our cloud identity provider service, Windows Live ID.

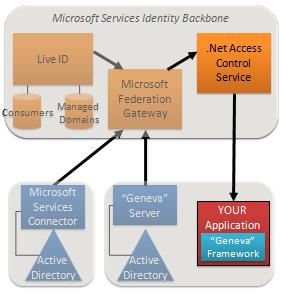

Microsoft also operates one of the largest Claims Providers in the world – our cloud identity provider service, Windows Live ID. We want to make it very easy for people to use our cloud applications and developer services without having to make any architectural decisions. So for that audience, we have built a fixed function server to federate Active Directory directly to the Microsoft Federation Gateway.

We want to make it very easy for people to use our cloud applications and developer services without having to make any architectural decisions. So for that audience, we have built a fixed function server to federate Active Directory directly to the Microsoft Federation Gateway. OK. This is all very nice for Microsoft's apps, but how do other application developers benefit?

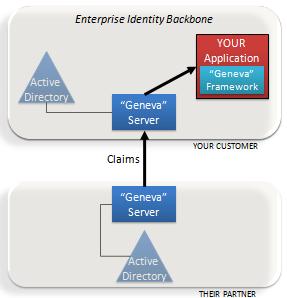

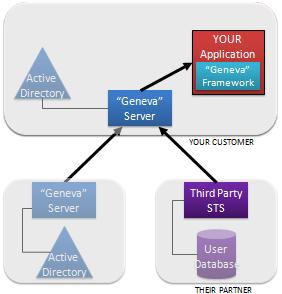

OK. This is all very nice for Microsoft's apps, but how do other application developers benefit? These benefits are a great demonstration of how well the claims model spans organizational boundaries. We really do move into a “write once and run anywhere” paradigm.

These benefits are a great demonstration of how well the claims model spans organizational boundaries. We really do move into a “write once and run anywhere” paradigm.

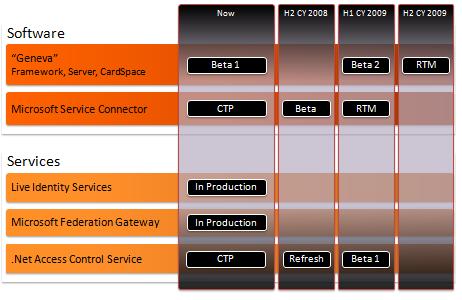

The “Geneva” Framework: A framework you use in your .Net application for handling claims. This was formerly called “Zermatt”.

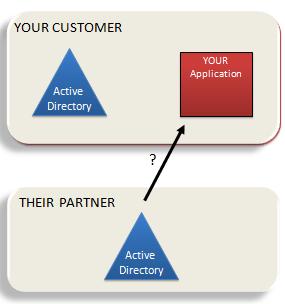

The “Geneva” Framework: A framework you use in your .Net application for handling claims. This was formerly called “Zermatt”. Anyone who has been around the block a few times knows there is one fatal flaw in the solution I’ve just described.

Anyone who has been around the block a few times knows there is one fatal flaw in the solution I’ve just described. I’m here today to tell you Microsoft has fully stepped up to the plate around federation. And it is already providing a lot of benefits and solving problems.

I’m here today to tell you Microsoft has fully stepped up to the plate around federation. And it is already providing a lot of benefits and solving problems. Whether you are creating serious Internet banking systems, hip new social applications, multi-party games or business applications for enterprise and government, you need to know something about the person using your application. We call this identity.

Whether you are creating serious Internet banking systems, hip new social applications, multi-party games or business applications for enterprise and government, you need to know something about the person using your application. We call this identity.