Stephan Engberg is member of the Strategic Advisory Board of the EU ICT Security & Dependability Taskforce and an innovator in terms of reconciling the security requirements in both ambient and integrated digital networks. I thought readers would benefit from comments he circulated in response to my posting on Touch2Id.

Kim Cameron's comments on Touch2Id – and especially the way PI is used – make me want to see more discussion about the definition of privacy and the approaches that can be taken in creating such a definition.

To me Touch2Id is a disaster – teaching kids to offer their fingerprints to strangers is not compatible with my understanding of democracy or of what constitutes the basis of free society. The claim that data is “not collected” is absurd and represents outdated legal thinking. Biometric data gets collected even though it shouldn't and such collection is entirely unnecessary given the PET solutions to this problem that exist, e. g chip-on-card.

In my book, Touch2Id did not do the work to deserve a positive privacy appraisal.

Touch2Id, in using blinded signature, is a much better solution than, for example, a PKI-based solution would be. But this does not change the fact that biometrics are getting collected where they shouldn't.

To me Touch2Id therefore remains a strong invasion of Privacy – because it teaches kids to accept biometric interactions that are outside their control. Trusting a reader is not an option.

My concern is not so much in discussing the specific solution as reaching some agreement on the use of words and what is acceptable in terms of use of words and definitions.

We all understand that there are different approaches possible given different levels of pragmatism and focus. In reality we have our different approaches because of a number of variables: the country we live in, our experiences and especially our core competencies and fields of expertise.

Many do good work from different angles – improving regulation, inventing technologies, debating, pointing out major threats etc. etc.

No criticism – only appraisal

Some try to avoid compromises – often at great cost as it is hard to overcome many legacy and interest barriers. At the same time the stakes are rising rapidly: reports of spyware are increasingly universal. Further, some try to avoid compromises out of fear or on the principle that governments are “dangerous”.

Some people think I am rather uncompromising and driven by idealist principles (or whatever words people use to do character assaination of those who speak inconvenient truths). But those who know me are also surprised – and to some extent find it hard to believe – that this is due largely to considerations of economics and security rather than privacy and principle.

Consider the example of Touch2Id. The fact that it is NON-INTEROPERABLE is even worse than the fact that biometrics are being collected, since because of this, you simply cannot create a PET solution using the technology interfaces! It is not open, but closed to innovations and security upgrades. There is only external verification of biometrics or nothing – and as such no PET model can be applied. My criticism of Touch2Id is fully in line with the work on security research roadmapping prior to the EU's large FP7 research programme (see pg. 14 on private biometrics and biometric encryption – both chip-on-card).

Some might remember the discussion at the 2003 EU PET Workshop in Brussels where there were strong objections to the “inflation of terms”. In particular, there was much agreement that the term Privacy Enhancing Technology should only be applied to non-compromising solutions. Even within the category of “non-compromising” there are differences. For example, do we require absolute anonymity or can PETs be created through specific built-in countermeasures such as anti-counterfeiting through self-incrimination in Digital Cash or some sort of tightly controlled Escrow (Conditional Identification) in cases such as that of non-payment in an otherwise pseudonymous contract (see here).

I tried to raise the same issue last year in Brussels.

The main point here is that we need a vocabulary that does not allow for inflation – a vocabulary that is not infected by someone's interest in claiming “trust” or overselling an issue.

And we first and foremost need to stop – or at least address – the tendency of the bad guys to steal the terms for marketing or propaganda purposes. Around National Id and Identity Cards this theft has been a constant – for example, the term “User-centric Identity” has been turned upside down and today, in many contexts, means “servers focusing on profiling and managing your identity.”

The latest examples of this are the exclusive and centralist european eID model and the IdP-centric identity models recently proposed by US which are neither technological interoperable, adding to security or privacy-enhancing. These models represent the latest in democratic and free markets failure.

My point is not so much to define policy, but rather to respect the fact that different policies at different levels cannot happen unless we have a clear vocabulary that avoid inflation of terms.

Strong PETs must be applied to ensure principles such as net neutrality, demand-side controls and semantic interoperability. If they aren't, I am personally convinced that within 20 or 30 years we will no longer have anything resembling democracy – and economic crises will worsen due to Command & Control inefficiencies and anti-innovation initiatives

In my view, democracy as construct is failing due to the rapid deterioration of fundamental rights and requirements of citizen-centric structures. I see no alternative than trying to get it back on track through strong empowerment of citizens – however non-informed one might think the “masses” are – which depends on propagating the notion that you CAN be in control or “Empowered” in the many possible meanings of the term.

When I began to think about Touch2Id it did of course occur to me that it would be possible for operators of the system to secretly retain a copy of the fingerprints and the information gleaned from the proof-of-age identity documents – in other words, to use the system in a deceptive way. I saw this as being something that could be mitigated by introducing the requirement for auditing of the system by independent parties who act in the privacy interests of citizens.

It also occured to me that it would be better, other things being equal, to use an on-card fingerprint sensor. But is this a practical requirement given that it would still be possible to use the system in a deceptive way? Let me explain.

Each card could, unbeknownst to anyone, be imprinted with an identifier and the identity documents could be surreptitiously captured and recorded. Further, a card with the capability of doing fingerprint recognition could easily contain a wireless transmitter. How would anyone be certain a card wasn't capable of surreptitiously transmitting the fingerprint it senses or the identifier imprinted on it through a passive wireless connection?

Only through audit of every technical component and all the human processes associated with them.

So we need to ask, what are the respective roles of auditability and technology in providing privacy enhancing solutions?

Does it make sense to kill schemes like Touch2ID even though they are, as Stephan says, better than other alternatives? Or is it better to put the proper auditing processes in place, show that the technology benefits its users, and continue to evolve the technology based on these successes?

None of this is to dismiss the importance of Stephan's arguments – the discussion he calls for is absolutely required and I certainly welcome it.

I'm sure he and I agree we need systematic threat analysis combined with analysis of the possible mitigations, and we need to evolve a process for evaluating these things which is rigorous and can withstand deep scrutiny.

I am also struck by Stephan's explanation of the relationship between interoperability and the ability to upgrade and uplevel privacy through PETs, as well as the interesting references he provides.

But then – the coup de grace. The privacy policy to which Apple redirects you is… are you ready… the same one we came across a few days ago at the App Store! So once again you need to get to the equivalent of page 37 of 45 to read:

But then – the coup de grace. The privacy policy to which Apple redirects you is… are you ready… the same one we came across a few days ago at the App Store! So once again you need to get to the equivalent of page 37 of 45 to read: “Today, I am pleased to announce the latest step in moving our Nation forward in securing our cyberspace with the release of the draft National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace (NSTIC). This first draft of NSTIC was developed in collaboration with key government agencies, business leaders and privacy advocates. What has emerged is a blueprint to reduce cybersecurity vulnerabilities and improve online privacy protections through the use of trusted digital identities. “

“Today, I am pleased to announce the latest step in moving our Nation forward in securing our cyberspace with the release of the draft National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace (NSTIC). This first draft of NSTIC was developed in collaboration with key government agencies, business leaders and privacy advocates. What has emerged is a blueprint to reduce cybersecurity vulnerabilities and improve online privacy protections through the use of trusted digital identities. “ I went to the Apple App store a few days ago to download a new iPhone application. I expected that this would be as straightforward as it had been in the past: choose a title, click on pay, and presto – a new application becomes available.

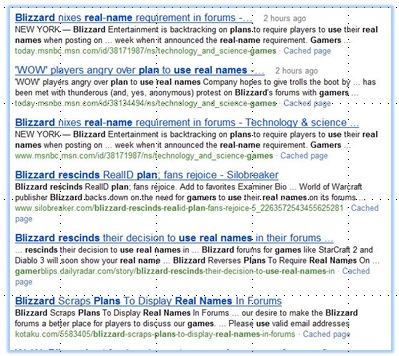

I went to the Apple App store a few days ago to download a new iPhone application. I expected that this would be as straightforward as it had been in the past: choose a title, click on pay, and presto – a new application becomes available. MSN

MSN