Since identity is a fundamental requirement of computing infrastructure, organizations have been involved in digital identity management for decades. Over the years, three models have emerged and co-existed. Of course I'm tempted to skip the history and jump headfirst into what's new and fresh today. But I think it is important to begin by reviewing the earlier models so we can get crisp about how the IdMaaS model differs from what has gone before. (Some day people who want to skip the previous models will be able to click here.)

Firewall Era Identity Model

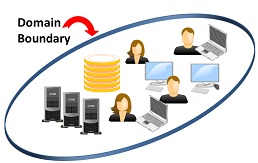

Enterprise identity technology evolved incrementally from mainframe days using the concept of administrative and security “domains”: collections of resources tightly integrated under a single, closed organizational administration.

Enterprise identity technology evolved incrementally from mainframe days using the concept of administrative and security “domains”: collections of resources tightly integrated under a single, closed organizational administration.

To control access to networks, computers, applications and information stores, it was necessary to identify them and recognize their legitimate users – whether people or software services. This required registration systems – often called directories – through which human and non-human identity records could be created, retrieved, updated and deleted (CRUD). In the domain paradigm identity management was thought to be the CRUD and little more.

While closed administrative domains were simple in theory, business requirements drove enterprises to adopt an assortment of unrelated internal systems and applications. Most came with their own independent user directories. Enterprises ended up with hundreds of different systems that had to be administered independently and would soon diverge.

With the advent of network PCs, we began to see Network Operating System domains that were collections of PC's working in conjunction with servers. Banyan‘s StreetTalk and Novell's Netware were both gamechanging products that introduced LAN directory coupled with identity management and authentication capabilities, but over time Active Directory achieved predominance as the administrative and security domain for PC users and applications. These products greatly simplified management of personal computers but the plethora of specialized business systems remained. In fact some enterprises ended up with multiple Active Directories.

A category of Identity Management integration products arose as a response to these problems: a dizzying array of often brittle point products and tools that could only be deployed at high cost by skilled specialists. They generally had to be customized to the point of being one-off solutions that paradoxically made the legacy even harder for customers to unravel.

In retrospect the most striking characteristic of the domain based model is that each domain spoke with absolute authority. It named things and asserted their attributes. The machines, services and administrators that were part of the domain took its assertions as being unquestionable. Trust for the domain was a condition of membership. There was no need for the evaluation of assertions since they came from the domain and the domain was right by definition.

Another characteristic was that each domain created identifiers within a namespace it controlled and they could be used to access the information about domain members and components by any entity the domain authorized. Systems typically employed a single namespace, and services used the same identifiers that were associated with domain components and users at authentication time.

In other words, until domains began to collide, it was a pretty simple world. Conversely, in todays interconnected and permeable world, most of the assumptions underlying the domain apply with growing caveats.

Internet-facing Identity Model

The explosion of the Internet surrounded the closed enterprise security domains with outward-facing systems aimed at customers and suppliers.

Once Web usage went beyond public applications like PR and advertising, organizations discovered that to enhance relationships with individual customers – and ultimately do e-Business – they needed ways to register them over the web. Customers and suppliers were seen as a different category of domain object, but the systems built for them still followed the domain model. Anything the domain said about its customer or supplier was taken to be true by all the applications in it.

Consumer and supply chain identity management was most often customized on top of existing business databases that were completely independent from the directories of employees maintained inside the corporate firewall.

This created problems in linking employees with customers. In the wake of mergers and acquisitions, companies struggled to deliver a unified experience to customers across multiple business units with diverse origins, and competition drove them to seek more unified identity and resource management services.

The Identity Management market thus expanded to include products that performed single sign-on and unified access control across a set of colliding domains, accompanied by large expenditures on hand-crafted integration projects.

Next: Identity Management before the cloud – the Identity Ecosystem Model

“the advent of network PCs” happened 15 years before Actice Directory was installed on its first network, Kim. At least give Novell (and Banyan) a little credit!

[Kim replies: Thanks Dave, BTW it would be interesting to hear your retrospective take on this period. It was an amazing time, and when I first wrote this post I skipped over the “process” and just described the end-state… For sure this left important things unsaid. So in response to your comment I've called out role of Banyan and Netware: they were great products produced by brilliant people – a number of whom remain my friends.]

I recalll “testing” Novelll and Banyan VINES in 1989. I'm pretty sure that it was 1990 when we bought our first ZOOMIT product for VINES.

While Domain Join may seem antiquated it sure does hide a lot of the mechanics and enable a lot of benefits – all with one teeny little command. Wouldn't it be nice if “New Domain Join” would automate all the mechanics of ADFS, provisioning, SSO, trust, etc?

I'm just looking for a new world where the mechanics have been hidden. Give me a New Domain Join, son of Domain Join.