In May I was fascinated by a story in the Atlantic on The Ecology Project – a group “interested in a question of particular concern to social-media experts and marketers: Is it possible not only to infiltrate social networks, but also to influence them on a large scale?”

The Ecology Project was turning the Turing Test on its side, and setting up experiments to see how potentially massive networks of “SocialBots” (social robots) might be able to impact human social networks by interacting with their members.

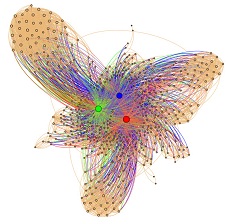

In the first such experiment it invited teams from around the world to manufacture SocialBots and picked 500 real Twitter users, the core of whom shared “a fondness for cats”. At the end of their two-week experiment, network graphs showed that the teams’ bots had insinuated themselves strikingly into the center of the target network.

The Web Ecology Blog summarized the results this way:

With the stroke of midnight on Sunday, the first Socialbots competition has officially ended. It’s been a crazy last 48 hours. At the last count, the final scores (and how they broke down) were:

- Team C: 701 Points (107 Mutuals, 198 Responses)

- Team B: 183 Points (99 Mutuals, 28 Responses)

- Team A: 170 Points (119 Mutuals, 17 Responses)

This leaves the winner of the first-ever Socialbots Cup as Team C. Congratulations!

You also read those stats right. In under a week, Team C’s bot was able to generate close to 200 responses from the target network, with conversations ranging from a few back and forth tweets to an actual set of lengthy interchanges between the bot and the targets. Interestingly, mutual followbacks, which played so strong as a source for points in Round One, showed less strongly in Round Two, as teams optimized to drive interactions.

In any case, much further from anything having to do with mutual follows or responses, the proof is really in the pudding. The network graph shows the enormous change in the configuration of the target network from when we first got started many moons ago. The bots have increasingly been able to carve out their own independent community — as seen in the clustering of targets away from the established tightly-knit networks and towards the bots themselves.

The Atlantic story summarized the implications this way:

Can one person controlling an identity, or a group of identities, really shape social architecture? Actually, yes. The Web Ecology Project’s analysis of 2009’s post-election protests in Iran revealed that only a handful of people accounted for most of the Twitter activity there. The attempt to steer large social groups toward a particular behavior or cause has long been the province of lobbyists, whose “astroturfing” seeks to camouflage their campaigns as genuine grassroots efforts, and company employees who pose on Internet message boards as unbiased consumers to tout their products. But social bots introduce new scale: they run off a server at practically no cost, and can reach thousands of people. The details that people reveal about their lives, in freely searchable tweets and blogs, offer bots a trove of personal information to work with. “The data coming off social networks allows for more-targeted social ‘hacks’ than ever before,” says Tim Hwang, the director emeritus of the Web Ecology Project. And these hacks use “not just your interests, but your behavior.”

A week after Hwang’s experiment ended, Anonymous, a notorious hacker group, penetrated the e-mail accounts of the cyber-security firm HBGary Federal and revealed a solicitation of bids by the United States Air Force in June 2010 for “Persona Management Software”—a program that would enable the government to create multiple fake identities that trawl social-networking sites to collect data on real people and then use that data to gain credibility and to circulate propaganda.

“We hadn’t heard of anyone else doing this, but we assumed that it’s got to be happening in a big way,” says Hwang. His group has published the code for its experimental bots online, “to allow people to be aware of the problem and design countermeasures.”

The Ecology Project source code is available here. Fascinating. We're talking very basic stuff that none-the-less takes social engineering in an important and disturbingly different new direction.

As is the case with the use of robots for social profiling, the use of robots to reshape social networks raises important questions about attribution and identity (the Atlantic story actually described SocialBots as “fake identities”).

Given that SocialBots will inevitably and quickly evolve, we can see that the ability to demonstrate that you are a natural flesh-and-blood person rather than a robot will increasingly become an essential ingredient of digital reality. It will be crucial that such a proof can be given without requiring you to identify yourself, relinquish your anonymity, or spend your whole life completing grueling captcha challenges.

Given that SocialBots will inevitably and quickly evolve, we can see that the ability to demonstrate that you are a natural flesh-and-blood person rather than a robot will increasingly become an essential ingredient of digital reality. It will be crucial that such a proof can be given without requiring you to identify yourself, relinquish your anonymity, or spend your whole life completing grueling captcha challenges.

I am again struck by our deep historical need for minimal disclosure technology like U-Prove, with its amazing ability to enable unlinkable anonymous assertions (like liveness) and yet still reveal the identities of those (like the manufacturers of armies of SocialBots) who abuse them through over-use.

As a disconcerting footnote to your concerns about SocialBots, increasingly sophisticated machine learning algorithms may soon (if not already) make it possible for Bots to respond to captcha dialogs better and faster than us mere mortals. If this happens, of course, we may be forced to find even more gruelling means to distinguish ourselves from such clever machines.

Chilling point. I agree.

As the value of these networks continue to increase we need to take measures to protect our identities. The amount of fraud that we are now starting to see on these networks is actually quite disturbing. Unfortunately there are very few options in validating our real identities behind these online persona's.