The software giant on Tuesday published the Microsoft Open Specification Promise, a document that says that Microsoft will not sue anyone who creates software based on Web services technology, a set of standardized communication protocols designed by Microsoft and other vendors.

What's new…

Microsoft has promised not to sue anyone who creates software based on Web services technology covered by patents it owns.

Bottom Line

The move reflects how Microsoft has had to come to terms with open-source products and development models.

Reaction to the surprise news was favorable, even from some of Microsoft's rivals.

“The best thing about this is the fundamental mind shift at Microsoft. A couple of years ago, this would have been unthinkable. Now it is real. This is really a major change in the way Microsoft deals with the open-source community,” said Gerald Beuchelt, a Web services architect working in the Business Alliances Group in Sun Microsystems’ chief technologist's office.

Microsoft has never sued anyone for patent infringement related to Web services. But its pledge not to assert the patents alleviates lingering concerns among developers who feared potential legal action if they incorporate Web services into their code, said analysts and software company executives.

Open-source developers, for example, should have fewer worries about writing open-source Web services products. Also, other software companies could create non-Windows products that interoperate with Microsoft code via Web services.

The move reflects how Microsoft has had to come to terms with open-source products and development models.

When Linux began to take hold in the late 1990s, company executives seemed shaken by the shared code foundations of the open-source model. CEO Steve Ballmer famously called Linux a “cancer,” while founder Bill Gates derided the “Pacman-like” nature of open-source licensing models.

Other Microsoft executives, such as Windows development leader Jim Allchin, have in years past painted open source as “an intellectual property destroyer.”

But in the past two years, Microsoft has stepped up its Shared Source program, in which it gives free access to source code under terms similar to those in popular open-source licenses. It has also said it will make Windows-based products work better with those from other vendors, including Linux and other open-source software.

Standards in play

To be sure, Microsoft, which spends more than $6 billion a year on research and development, remains committed to generating proprietary intellectual property. In some cases, that means commercial licensing, rather than opening up access to others.

“In the future, I am sure we will take positions on IP (intellectual property) that will not be so agreeable to various constituencies,” wrote Jason Matusow, Microsoft's director of standards affairs, in his blog.

In the case of Web services, having a pledge not to assert patents around these protocols–which are the communications foundation of Vista, the next version of Windows due early next year–helps drive adoption of those standards in the marketplace, said analysts and software company executives.

Open-source projects, in particular, have become powerful forces within the industry for establishing standards, both de facto and those sanctioned by standards bodies.

“I expect that more and more vendors will realize that a software standard cannot be successful if the relevant patents are incompatible with open-source licenses and principles,” said Cliff Schmidt, vice president of legal affairs at the Apache Software Foundation, which hosts several open-source projects.

Patent pledges of various forms have become more common, he noted. Sun recently said that it would not assert patents relating to the SAML (Security Assertion Markup Language) standard and the OpenDocument Format. IBM gave open-source communities access to 500 patents last year.

More to come?

Microsoft's Matusow said that the Open Specification Promise is part of the company's efforts to “think creatively about intellectual property.”

For the Open Specification Promise, the company sought input from open-source legal experts, including Red Hat's deputy general counsel Mark Webbink and Lawrence Rosen, an open-source software lawyer at Rosenlaw & Einschlag in Northern California.

Matusow said Microsoft is still a big believer in intellectual property but added that the company has chosen a “spectrum approach” to it, which ranges from traditional IP licensing to more permissive usage terms that mimic open-source practices.

“That is the point of a spectrum approach. Any–and I do mean any–commercial organization today needs to have a sophisticated understanding of intellectual property and the strategies you may employ with it to achieve your business goals,” he said.

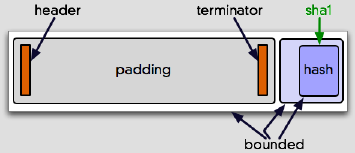

The current Open Specification Promise does not specifically cover CardSpace, formerly called InfoCard. But the promise not to assert patents could be extended from current Web services standards, said Michael Jones, Microsoft's director of distributed systems customer strategy and evangelism.

“Licensing additional specifications under these same terms should be much easier to do at this point, but I obviously can't make public commitments yet beyond those we already have buy-off on,” Jones said on a discussion group at OSIS, the open-source identity selector project.

Old concerns

Web services standards are authored by several vendors, often including Microsoft and IBM, and are built into products from many vendors.

IBM lauded the move in a statement on Wednesday. “We've provided open-source friendly licenses for Web services specifications and have made non-assert commitments for a broad set of open-source projects including Linux,” said Karla Norsworthy, vice president for software standards at IBM.

Web services specifications are standardized in the World Wide Web Consortium and in the Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards. Both bodies allow people to license standards either royalty-free or on so-called RAND terms (reasonable and non-discriminatory terms).

But Microsoft's Open Specification Promise goes a bit further. It means that developers at Apache projects, for example, no longer have to worry about Microsoft asserting Web services patents down the road, said Apache's Schmidt.

Similarly, Rosen said that the “OSP is compatible with free and open-source licenses.”

That clarity is a far cry from the early days of Web services, which took shape around 2000, when Microsoft and IBM teamed with others to improve system interoperability using XML-based protocols.

Lingering concerns remained among outside developers and were points of dispute in some Web services standardization efforts.

In 2000, Anne Thomas Manes was the chief technology officer of a Web services start-up called Systinet. The venture capitalist backers of the company were nervous that implementing these newly published specifications, created by other companies, could lead to lawsuits down the road, she said.

Until now, there was still a “niggling concern” that Microsoft would sue people. Back in 2000, Systinet decided to accept the risk of creating software based on specifications created by others, even though they did not have a license, she said.

“We went ahead and did it anyway despite the risk, because we were of the impression that Microsoft and IBM really wanted people to implement it,” she said.

To me it isn't really very surprising that Microsoft is doing everything it can to co-operate with everyone else in the industry on fundamental infrastructure like identity and web service protocols. It suddenly seems like this is being made into a bigger deal than it really is. That said, I'm really glad that lingering doubts about our intentions are dissipating.