Axel Nennker of Ignisvulpis writes, “Wordling things seems to be á la mode. I could not resist to wordle Kim Cameron‘s Seven Laws of Identity….”

Thanks Axel. This pretty much sums it up.

Axel Nennker of Ignisvulpis writes, “Wordling things seems to be á la mode. I could not resist to wordle Kim Cameron‘s Seven Laws of Identity….”

Thanks Axel. This pretty much sums it up.

It's a great day for Information Cards, Internet security and privacy. I can't put it better than this:

June 24, 2008 – Australia, Canada, France, Germany, India, Sri Lanka, United Kingdom, United States – An array of prominent names in the high-technology community today announced the formation of a non-profit foundation, The Information Card Foundation, to advance a simpler, more secure and more open digital identity on the Internet, increasing user control over their personal information while enabling mutually beneficial digital relationships between people and businesses.

Led by Equifax, Google, Microsoft, Novell, Oracle, and PayPal, plus nine leaders in the technology community, the group established the Information Card Foundation (ICF) to promote the rapid build-out and adoption of Internet-enabled digital identities using Information Cards.

Information Cards take a familiar off-line consumer behavior – using a card to prove identity and provide information – and bring it to the online world. Information Cards are a visual representation of a personal digital identity which can be shared with online entities. Consumers are able to manage the information in their cards, have multiple cards with different levels of detail, and easily select the card they want to use for any given interaction.

“Rather than logging into web sites with usernames and passwords, Information Cards let people ‘click-in’ using a secure digital identity that carries only the specific information needed to enable a transaction,” said Charles Andres, executive director for the Information Card Foundation. “Additionally, businesses will enjoy lower fraud rates, higher affinity with customers, lower risk, and more timely information about their customers and business partners.”

The founding members of the Information Card Foundation represent a wide range of technology, data, and consumer companies. Equifax, Google, Microsoft, Novell, Oracle, and PayPal, are founding members of the Information Card Foundation Board of Directors. Individuals also serving on the board include ICF Chairman Paul Trevithick of Parity, Patrick Harding of Ping Identity, Mary Ruddy of Meristic, Ben Laurie, Andrew Hodgkinson of Novell, Drummond Reed, Pamela Dingle of the Pamela Project, Axel Nennker, and Kim Cameron of Microsoft.

“The creation of the ICF is a welcome development,” said Jamie Lewis, CEO and research chair of Burton Group. “As a third party, the ICF can drive the development of Information Card specifications that are independent of vendor implementations. It can also drive vendor-independent branding that advertises compliance with the specifications, and the behind-the-scenes work that real interoperability requires.”

The Information Card Foundation will support and guide industry efforts to enable the development of an open, trusted and interoperable identity layer for the Internet that maximizes control over personal information by individuals. To do so, the Information Card infrastructure will use existing and emerging data exchange and security protocols, standards and software components.

Businesses and organizations that supply or consume personal information will benefit from joining the Information Card Foundation to improve their trusted relationships with their users. This includes financial institutions, retailers, educational and government institutions, healthcare providers, retail providers, travel, entertainment, and social networks.

The Information Card Foundation will hold interoperability events to improve consistency on the web for people using and managing their Information Cards. The ICF will also promote consistent industry branding that represents interoperability of Information Cards and related components, and will promote identity policies that protect user information. This branding and policy development is designed to give all Internet users confidence that they can exert greater control over personal information released to specific trusted providers through the use of Information Cards.

“Liberty Alliance salutes the open industry oversight of Information Card interoperability that the formation of ICF signifies,” said Brett McDowell, executive director, Liberty Alliance. “Our shared goal is to deliver a ubiquitous, interoperable, privacy-respecting federated identity layer as a means to seamless, secure online transactions over network infrastructure. We look forward to exploring with ICF the expansion of the Liberty Alliance Interoperable(tm) testing program to include Information Card interoperability as well as utilization of the Identity Assurance Framework across Information Card deployments.”

As part of its affiliations with other organizations, The Information Card Foundation has applied to be a working group of Identity Commons, a community-driven organization promoting the creation of an open identity layer for the Internet while encouraging the development of healthy, interoperable communities.

Additional founding members are Arcot Systems,Aristotle, A.T.E. Software, BackgroundChecks.com, CORISECIO, FuGen Solutions, the Fraunhofer Institute, Fun Communications, the Liberty Alliance, Gemalto, IDology, IPcommerce, ooTao, Parity, Ping Identity, Privo, Wave Systems, and WSO2

Further information about the Information Card Foundation can be found at www.informationcard.net.

I enjoy having been invited to join the foundation board as one of the representatives of the identity community, rather than as a corporate representative (Mike Jones will play that role for Microsoft). Beyond the important forces involved, this is a terrific group of people with deep experience, and I look forward to what we can achieve together.

One thing for sure: the Identity Big Bang is closer than ever. Given the deep synergy between OpenID and Information Cards, we have great opportunities all across the identity spectrum.

We know how the web feeds itself in a chain reaction powered by the assembly and location of information. We love it. Bringing information together that was previously compartmentalized has made it far easier to find out what is happening and avoid thinking narrowly. In some cases it has even changed the fundamentals of how we work and interact. The blogosphere identity conversation is an example of this. We are able to learn from each other across the industry and adjust to evolving trends in a fluid way, rather than “projecting” what other peoples’ thinking and motivations might be. In this sense the content of what we are doing is related to the medium through which we do it.

Information accumulates power by being put into proximity and aggregated. This even appears to be an inherent property of information itself. Of course information can't effect its own aggregation, but easily finds hosts who are motivated to do so: businesses, governments, researchers, industries, libraries, data centers – and the indefatigable search engine.

Some forms of aggregation involve breaking down the separation between domains of facts. Facts are initially discerned within a context. But as contexts flow together and merge , the facts are visible from new perspectives. We can think of them as “views”.

Information trends and digital identity

How does this fundamental tendency of information to reorganize itself relate to digital identity?

This is clearly a complicated question. But it is perhaps one of the most important questions of our time – one that needs to come to the attention of students, academics, policy makers, legislators, and through them, the general public. The answer will affect everyone.

It is hard to clearly explain and discuss trends that are so infrastructural. Those of us working on these issues have concepts that apply, but the concepts don't really have satisfactory names, and just aren't crisp enough. We aren't ready for a wider conversation about the things we have seen.

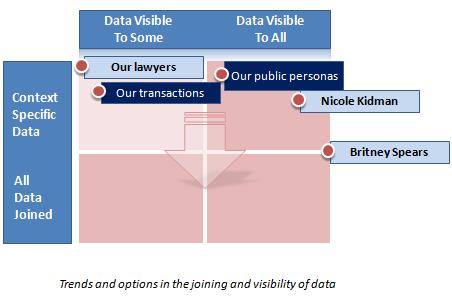

Recently I've been trying to organize my own thinking about this through a grid expressing, on one axis, the tendency of context to merge; and, on the other, the spectrum of data visibility:

The spectrum of visibility extends from a single individual on the left to everyone in the society on the right [if reading a text feed please check the graphic – Kim].

The spectrum of contextual separation extends from complete separation of information by context at the top, to complete joining of data across contexts at the bottom.

I've represented the tendency of information to aggregate as the arrow leading from separation to full join, and this should be considered a dynamic tendency of the system.

Where do we fit in this picture?

Now lets set up a few markers from which we can calibrate this field. For example, let's take what I've labelled “Today's public personas”. I'm talking about what we reveal about ourselves in the public realm. Because it's public, it's on the “Visible to all” part of the spectrum. Yet for most of us, it is a relatively narrow set of information that is revealed – our names, property we own, aspects of our professional lives. Thus our public personas remain relatively contextual.

You can imagine variants on this – for example a show-business personality who might be situated further to the right than the “public persona”, being known by more people. Further, additional aspects of such a person's life might be known, which would be represented by moving down towards the bottom of the quadrant (or even further).

I've also included a marker that represents the kind of commercial relationships encountered in today's western society. Now we're on the “Visible to some” part of the visibility spectrum. In some cases (e.g. our dealings with lawyers), this marker would hopefully be located further to the left, indicating fewer parties to the information. The current location implies some overlapping of context and sharing across parties – for example, transactions visible to credit card companies, merchants, and third parties in their employ.

Going forward, I'll look at what happens as the dynamic towards data joining asserts itself in this model.

Ping's Andre Durand has announced an award that not only says good things about his company, but is a crystal clear indication of the importance federated identity technology will inevitably acquire as people adopt it:

“A few days ago Morgan Stanley awarded Ping their CTO Summit Innovation Award. Ping was the sole recipient of this years award, which recognizes those which hold the promise of potentially transforming Morgan Stanley’s business. VMware won the award in 2005 — we really like that comparison! Who knew virtualization was going to be as big as it is today 3 or 4 years ago?

“Every year Morgan Stanley receives around 200 applications from companies to present at their CTO Summit. They internally vote and select 36 to present. Of these, only four ever get as far as contracts and of those, only one receives this award. We presented Ping Identity and our product, PingFederate back in 2006 (is the ulterior motive obvious enough?). As hoped, earlier this year Morgan Stanley became a customer, using our technology to secure and integrate their employees’ use of on-demand applications such as Salesforce.com among other things.

“It’s great to finally see identity federation receive the recognition it deserves for enabling companies to secure their virtual borders. It’s going to be a good year!”

Ping's success doesn't surprise me given the high standards it sets itself. And we all expect Morgan Stanley's CTO to be forward-thinking and “on the money”, so to speak.

But still, this is a remarkable bellwether in so clearly recognizing the transformative nature of identity. Congratulations are due both to Ping and to Jonathan Saxe, Managing Director, Global Chief Information Officer of Morgan Stanley.

Ryan Janssen at drstarcat.com published an interview recently that led me to think back over the various phases of my work on identity. I generally fear boring people with the details, but Ryan explored some things that are very important to me, and I appreciate it.

After talking about some of the identity problems of the enterprise, he puts forward a description of metadirectory that I found interesting because it starts from current concepts like claims rather than the vocabulary of X.500:

…. Kim and the ZOOMIT team came up with the concept of a “metadirectory”. Metadirectory software essentially tries to find correlation handles (like a name or email) across the many heterogeneous software environments in an enterprise, so network admins can determine who has access to what. Once this is done, it then takes the heterogeneous claims and transforms them into a kind of claim the metadirectory can understand. The network admin can then use the metadirectory to assign and remove access from a single place.

Zoomit released their commercial metadirectory software (called “VIA”) in 1996 and proceeded to clean the clock of larger competitors like IBM for the next few years until Microsoft acquired the company in the summer of 1999. Now anyone who is currently involved in the modern identity movement and the issues of “data portability” that surround it has to be feeling a sense of deja vu because these are EXACTLY the same problems that we are now trying to solve on the internet—only THIS time we are trying to take control of our OWN claims that are spread across innumerable heterogeneous systems that have no way to communicate with each other. Kim’s been working on this problem for SIXTEEN years—take note!

Yikes. Time flies when you're having fun.

When I asked Kim what his single biggest realization about Identity in the 16 years since he started working on it was, he was slow to answer, but definitive when he did—privacy. You see, Kim is a philosopher as well as a technologist. He sees information technology (and the Internet in particular) as a social extension of the human mind. He also understands that the decisions we make as technologists have unintended as well as intended consequences. Now creating technology that enables a network administrator to understand who we are across all of a company’s systems is one thing, but creating technology that allows someone to understand who we are across the internet, particularly as more and more of who we are as humans is stored there, and particularly if that someone isn’t US or someone we WANT to have that complete view, is an entirely other problem.

Kim has consistently been one the strongest advocates for obscuring ANY correlation handles that would allow ANY Identity Provider or Relying Party to have a more complete view of us than we explicitly give them. Some have criticized his concerns as overly cautious in a world where “privacy is dead”. When you think of your virtual self as an extension of your personal self though, and you realize that the line between the two is becoming increasingly obscured, you realize that if we lose privacy on the internet, we, in a very real sense, lose something that is essentially human. I’m not talking about the ability to hide our pasts or to pretend to be something we’re not (though we certainly will lose that). What we lose is that private space that makes each of us unique. It’s the space where we create. It’s the space that continues to ensure that we don’t all collapse into one.

Yes, it is the space on which and through which Civilization has been built.

Kuppinger Cole‘s analyst Felix Gaehtgens calls on Microsoft to move more quickly in announcing how we are going to make Credentica's Minimal Disclosure technology available to others in the industry. He says,

“On March 6th, almost a month ago, Microsoft announced its acquisition of Montreal based Credentica, a technology leader in the online digital privacy area. It’s been almost a month, but the dust won’t settle. Most analysts including KCP agree that Microsoft has managed a master coup in snapping up all patents and rights to this technology. But there are fears in the industry that Microsoft could effectively try to use this technology to enrich its own platform whilst impeding interoperability by making the technology unavailable. These fears are likely to turn out to be unfounded, but Microsoft isn’t helping to calm the rumour mill – no statements are being made for the time being to clarify its intentions.”

Wow. Felix makes a month sound like such a long time. I'm jealous. To me it just flew by. But I get his message and feel the tines of his pitchfork.

Calling U-Prove a “Hot Technology” and explaining why, Felix continues,

“…if Microsoft were to choose to leverage the technology only in its own ecosystem, effectively shutting out the rest of the Internet, then it would be very questionable whether the technology would be widely adopted. The same if Microsoft were to release the specifications, but introduce a “poison pill” by leveraging its patent. This would certainly be against Microsoft’s interest in the medium to long future.”

This is completely correct. Microsoft would have to be completely luny to try to partition the internet across vendor lines. So, basically, you can be sure we won't.

“There is a fair amount of mistrust in the industry, sometime even bordering on paranoia because of Microsoft’s past approach to privacy and interoperability. The current heated discussion about the OOXML is an example of this. Over the last years, Microsoft has taken great pains to alleviate those fears, and has shown an willingness to work towards interoperability. But many are not yet convinced of the picture that Kim is painting. It is very much in Microsoft’s interest to make an official statement regarding its broad intentions with U-Prove, and reassure the industry if and how Microsoft intends to follow the “fifth law of identity” with regards to this new technology.

We are working hard on this. The problem is that Microsoft can't make an announcement until we have the legal documents in place to show what we're talking about. So there is no consipiracy or poison pill. Just a lot of details to nail down.

The Law of User Control is hard at work in a growing controversy about interception of people's web traffic in the United Kingdom. At the center of the storm is the “patent-pending” technology of a new company called Phorm. It's web site advises:

Leading UK ISPs BT, Virgin Media and TalkTalk, along with advertisers, agencies, publishers and ad networks, work with Phorm to make online advertising more relevant, rewarding and valuable. (View press release.)

Phorm's proprietary ad serving technology uses anonymised ISP data to deliver the right ad to the right person at the right time – the right number of times. Our platform gives consumers advertising that's tailored to their interests – in real time – with irrelevant ads replaced in the process.

What makes the technology behind OIX and Webwise truly groundbreaking is that it takes consumer privacy protection to a new level. Our technology doesn't store any personally identifiable information or IP addresses, and we don't retain information on user browsing behaviour. So we never know – and can't record – who's browsing, or where they've browsed.

It is counterintuitive to see claims of increased privacy posited as the outcome of a tracking system. But even if that happened to be true, it seems like the system is being laid on the population as a fait accompli by the big powerful ISPs. It doesn't seem that users will be able to avoid having their traffic redirected and inspected. And early tests of the system were branded “illegal” by Nicholas Bohm of the Foundation for Information Policy Research (FIPR).

Is Phorm completely wrong? Probably not. Respected and wise privacy activist Simon Davies has done an Interim Privacy Impact Assessment that argues (in part):

In our view, Phorm has successfully implemented privacy as a key design component in the development of its Phorm Technology system. In contrast to the design of other targeting systems, careful choices have been made to ensure that privacy is preserved to the greatest possible extent. In particular, Phorm has quite consciously avoided the processing of personally identifiable information.

Simon seems to be suggesting we consider Phorm in relation to the current alternatives – which may be worse.

To make a judgment we need to really understand how Phorm's system works. Dr. Richard Clayton, a computer security researcher at the University of Cambridge and a participant in Light Blue Touchpaper, has published a succinct ten page explanation that that is a must-read for anyone who is a protocol head.

Richard says his technical analysis of the Phorm online advertising system has reinforced his view that it is “illegal”, breaking laws designed to limit unwarranted interception of data.

The British Information Commissioners Office confirmed to the BBC that BT is planning a large-scale trial of the technology “involving around 10,000 broadband users later this month”. The ICO said: “We have spoken to BT about this trial and they have made clear that unless customers positively opt in to the trial their web browsing will not be monitored in order to deliver adverts.”

Having quickly read Richard's description of the actual protocol, it isn't yet clear to me that if you opt out, your web traffic isn't still being examined and redirected. But there is worse. I have to admit to a sense of horror when I realized the system rewards ISPs for abusing their trusted role in the Internet by improperly posing as other peoples’ domains in order to create fraudulent cookies and place them on users machines. Is there a worse precedent? How come ISPs can do this kind of thing and other can't? Or perhaps now they can…

To accord with the Laws of Identity, no ISP would examine or redirect packets to a Phorm-related server unless a user explicitly opted-in to such a service. Opting in should involve explicitly accepting Phorm as a justifiable witness to all web interactions, and agreeing to be categorized by the Phorm systems.

The system is devised to aggregate across contexts, and thus runs counter to the Fourth Law of Identity. It claims to mitigate this by reducing profiling to categorization information. However, I don't buy that. Categorization, practiced at a grand enough scale and over a sufficient period of time, potentially becomes more privacy invasive than a regularly truncated audit trail. Thus there must be mechanisms for introducing amnesia into the categorization itself.

Phorm would therefore require clearly defined mechanisms for deprecating and deleting profile information over time, and these should be made clear during the opt-in process.

I also have trouble with the notion that in Phorm identities are “anonymized”. As I understand it, each user is given a persistent random ID. Whenever the user accesses the ISP, the ISP can see the link between the random ID and the user's natural identity. I understand that ISPs will prevent Phorm from knowing the user's natural identity. That is certainly better than many other systems. But I still wouldn't claim the system is based on anonymity. It is based on controlling the release of information.

[Podcasts are available here]

Vikram Kumar works for New Zealand's State Services Commission on the All-of-government Authentication Programme. As he puts it, “… that means my working and blog lives intersect….” In this discussion of the Third Law of Identity, he argues that in New Zealand, where the population of the whole country is smaller than that of many international cities, people may consider the government to be a “justifiable party” in private sector transactions:

A recent article in CR80News called Social networking sites have little to no identity verification got me thinking about the Laws of Identity, specifically Justifiable Parties, “Digital identity systems must be designed so the disclosure of identifying information is limited to parties having a necessary and justifiable place in a given identity relationship.”

The article itself makes points that have been made before, i.e. on social networking sites “there’s no way to tell whether you’re corresponding with a 15-year-old girl or a 32-year-old man…The vast majority of sites don’t do anything to try to confirm the identities of members. The sites also don’t want to absorb the cost of trying to prove the identity of their members. Also, identifying minors is almost impossible because there isn’t enough information out there to authenticate their identity.”

In the US, this has thrown up business opportunities for some companies to act as third party identity verifiers. Examples are Texas-based Entrust, Dallas-based RelyID, and Atlanta-based IDology. They rely on public and financial records databases and, in some cases, government-issued identification as a fallback.

Clearly, these vendors are Justifiable Parties.

What about the government? It is the source of most of the original information. Is the government a Justifiable Party?

In describing the law, Kim Cameron says “Today some governments are thinking of operating digital identity services. It makes sense (and is clearly justifiable) for people to use government-issued identities when doing business with the government. But it will be a cultural matter as to whether, for example, citizens agree it is “necessary and justifiable” for government identities to be used in controlling access to a family wiki or connecting a consumer to her hobby or vice.” [emphasis added]

So, in the US, where there isn’t a high trust relationship between people and the government, the US government would probably not be a Justifiable Party. In other words, if the US government was to try and provide social networking sites with the identity of its members, the law of Justifiable Parties predicts that it would fail.

This is probably no great discovery- most Americans would have said the conclusion is obvious, law of Justifiable Parties or not.

Which then leads to the question of other cultures…are there cultures where government could be a Justifiable Party for social networking sites?

To address, I think it is necessary to distinguish between the requirements of social networking sites that need real-world identity attributes (e.g. age) and the examples that Kim gives- family wiki, connecting a consumer to her hobby or vice- where authentication is required (i.e. it is the same person each time without a reliance on real-world attributes).

Now, I think government does have a role to play in verifying real-world identity attributes like age. It is after all the authoritative source of that information. If a person makes an age claim and government accepts it, government-issued documents reflects the accepted claim as, what I call, an authoritative assertion that other parties accept.

The question then is whether in some high trust societies, where there is a sufficiently high trust relationship between society and government, can the government be a Justifiable Party in verifying the identity (or identity attributes such as age alone) for the members of social networking societies?

I believe that the answer is yes. Specifically, in New Zealand where this trust relationship exists, I believe it is right and proper for government to play this role. It is of course subject to many caveats, such as devising a privacy-protective system for the verification of identity or identity attributes and understanding the power of choice.

In NZ, igovt provides this. During public consultation held late last year about igovt, people were asked whether they would like to use the service to verify their identity to the private sector (in addition to government agencies). In other words, is government a Justifiable Party?

The results from the public consultation are due soon and will provide the answer. Based on the media coverage of igovt so far, I think the answer, for NZ, will be yes, government is a Justifiable Party.

It is noteworthy that if citizens give them the go-ahead, the State Services Commission is prepared to take on the responsibility and risk of managing all aspects of the digital identity of New Zealand's citizens . The combined governement and commercial identities the Commission administers will attract attackers. Effectively, the Commission will be handling “digital explosives” of a greater potency than has so far been the case anywhere in the world.

At the same time, the other Laws of Identity will continue to hold. The Commission will need to work extra hard to achieve data minimization after having collapsed previously independent contexts together. I think this can be done, but it requires tremendous care and use of the most advanced policies and technologies.

To be safe, such an intertwined system must, more than any other, minimize disclosure and aggregation of information. And more than any other, it must be resilient against attack.

If I lived in New Zealand I would be working to see that the Commission's system is based on a minimal disclosure technology like U-Prove or Idemix. I would also be working to make sure the system avoids “redirection protocols” that give the identity provider complete visibility into how identity is used. (Redirection protocols unsuitable for this usage include SAML and WS-Federation, as well as OpenID). Finally, I would make phishing resistance a top priority. In short, I wouldn't touch this kind of challenge without Information Cards and very distributed, encrypted information storage.

Novell's Dale Olds, who will be on Dave Kearns’ panel at the upcoming European Identity Conference, has added the “identity bus” to the metadirectory / virtual directory mashup. He says in part :

Meta directories synchronize the identity data from multiple sources via a push or pull protocols, configuration files, etc. They are useful for synchronizing, reconciling, and cleaning data from multiple applications, particularly systems that have their own identity store or do not use a common access mechanism to get their identity data. Many of those applications will not change, so synchronizing with a metadirectory works well.

Virtual directories are useful to pull identity data through the hub from various sources dynamically when an application requests it. This is needed in highly connected environments with dynamic data, and where the application uses a protocol which can be connected to the virtual directory service. I am also well aware that virtual directory fans will want to point out that the authoritative data source is not the service itself, but my point here is that, if the owners shut down the central service, applications can’t access the data. It’s still a political hub.

Personally, I think all this meta and virtual stuff are useful additions to THE key identity hub technology — directory services. When it comes to good old-fashioned, solid scalable, secure directory services, I even have a personal favorite. But I digress.

The key point here as I see it is ‘hub’ vs. ‘bus’ — a central hub service vs. passing identity data between services along the bus.

The meta/virtual/directory administration and configuration is the limiting problem. In directory-speak, the meta/virtual/directory must support the union of all schema of all applications that use it. That means it’s not the mass of data, or speed of synchronization that’s the problem — it’s the political mass of control of the hub that becomes immovable as more and more applications rendezvous on it.

A hub is like the proverbial silo. In the case of meta/virtual/directories the problem goes beyond the inflexibility of large identity silos like Yahoo and Google — those silos support a limited set of very tightly coupled applications. In enterprise deployments, many more applications access the same meta/virtual/directory service. As those applications come and go, new versions are added, some departments are unwilling to move, the central service must support the union of all identity data types needed by all those applications over time. It’s not whether the service can technically achieve this feat, it’s more an issue of whether the application administrators are willing to wait for delays caused by the political bottleneck that the central service inevitably becomes.

Dale makes other related points that are well worth thinking about. But let me zoom in on the relation between metadirectory and the identity bus.

As Dale points out in his piece, I think of the “bus” as being a “backplane” loosely connecting distributed services. The bus exends forever in all directions, since ultimately distributed computing doesn't have a boundary.

In spite of this, the fabric of distributed services isn't an undifferentiated slate. Services and systems are grouped into continents by the people and organizations running and using them. Let's call these “administrative domains”. Such domains may be defined at any scale – and often overlap.

The magic of the backplane or “bus”, as Stuart Kwan called it, is that we can pass identity claims across loosely coupled systems living in multiple discontinuous administrative domains.

But let's be clear. The administrative domains still continue to exist, and we need to manage and rationalize them as much tomorrow as we did yesterday.

I see metadirectories (meaning directories of directories) as the glue for stitching up these administrative continents so digital objects can be managed and co-ordinated within them.

That is the precondition for hoisting the layer of loosely coupled systems that exists above administrative domains. And I don't think it matters one bit whether a given digital object is accessed by a remote protocol, synchronization, or stapling a set of claims to a message – each has its place.

Complex and interesting issues. And my main concern here is not terminology, but making sure the things we have learned about metadirectory (or whatever you want to call it) are properly integrated into the evolving distributed computing architecture. A lot of us are going to be at the European Identity Conference in Munich later this month, so I look forward to the sessions and discussions that will take place there.

You have to like the way, in his latest piece on metadirectory, Dave Kearns summons Lewis Carroll to chide me for using the word “metadirectory” to mean whatever I want:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is, ” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty. “which is to be master—that's all.

Dave continues:

Kim talks about a “second generation” metadirectory. Metadirectory 2.0 if you will. First time I've heard about it. First time anyone has heard about it, for that matter. There is no such animal. Every metadirectory on the market meets the definition which Kim provides as “first generation”.

It's time to move on away from the huge silo that sucks up data, disk space, RAM and bandwidth and move on to a more lithe, agile, ubiquitous and pervasive identity layer. Organized as an identity hub which sees all of the authoritative sources and delivers, via the developer's chosen protocol, the data the application needs when and where it's needed.

It's funny. I remember sitting around in Craig Burton's office in 1995 while he, Jamie Lewis and I tried to figure out what we should call the new kind of multi-centered logical directory that each of us had come to understand was needed for distributed computing.

After a while, Craig threw out the word “metadirectory”. I was completely amazed. My colleagues and I had also come up with the word “metadirectory”, but we figured the name would be way too “intellectual” – even though the idea of a “directory of directories” was exactly right.

Craig just laughed the way he always does when you say something naive. Anyone who knows Craig will be able to hear him saying, “Kim, we can call it whatever we want. If we call it what it really is, how can that be wrong?”

So guess what? The thing we were calling a metadirectory was a logical directory, not a physical one. We figured that the output of one instance was the input to the next – there was no center. The metadirectory would speak all protocols, support different technologies and schemas, support referral to specific application directories, and preserve the application-related characteristics of the constituent data stores. I'll come back to these ideas going forward because I think they are still super important.

My message to Dave is that I haven't changed what I mean by metadirectory one iota since the term was first introduced in 1995. I've always seen what is now called virtual directory as an aspect of metadirectory. In fact, I shipped a product that included virtual directory in 1996. It not only synchronized, but it did what we used to call “chaining” and “referral” in order to create composite views across multiple physical directories. It did this not only at the server, but optionally on the client.

Of course, there were implementations of metadirectory that were “a bit more focussed”. Customers put specific things at the top of their list of “must-haves”, and that is what everyone in the industry tried to build.

But though certain features predominated in the early days of metadirectory, that doesn't mean that those features ARE metadirectory. We still live in the age of the logical directory, and ALL the aspects of the metadirectory that address that fact will continue to be important.

[Read the rest of Dave's post here.]