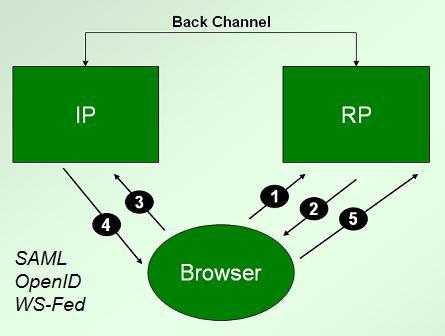

Moving on from certificates in our examination of identity technology and linkability, we'll look next at the redirection protocols – SAML, WS-Federation and OpenID. These work as shown in the following diagram. Let's take SAML as our example.

In step 1, the user goes to a relying party and requests a resource using an http “GET”. Assuming the relying party wants proof of identity, it returns 2), an http “redirect” that contains a “Location” header. This header will necessarily include the URL of the identity provider (IP), and a bunch of goop in the URL query string that encodes the SAML request.

For example, the redirect might look something like this:

HTTP/1.1 302 Object Moved

Date: 21 Jan 2004 07:00:49 GMT

Location:

https://ServiceProvider.com/SAML/SLO/Browser?SAMLRequest=fVFdS8MwFH0f7D%

2BUvGdNsq62oSsIQyhMESc%2B%2BJYlmRbWpObeyvz3puv2IMjyFM7HPedyK1DdsZdb%........2F%

50sl9lU6RV2Dp0vsLIy7NM7YU82r9B90PrvCf85W%2FwL8zSVQzAEAAA%3D%

3D&RelayState=0043bfc1bc45110dae17004005b13a2b&SigAlg=http%3A%2F%

2Fwww.w3.org%2F200%2F09%2Fxmldsig%23rsasha1&

Signature=NOTAREALSIGNATUREBUTTHEREALONEWOULDGOHERE

Content-Type: text/html; charset=iso-8859-1

The user's browser receives the redirect and then behaves as a good browser should, doing the GET at the URL represented by the Location header, as shown in 3).

The question of how the relying party knows which identity provider URL to use is open ended. In a portal scenario, the address might be hard wired, pointing to the portal's identity provider. Or in OpenID, the user manually enters information that can be used to figure out the URL of the identity provider (see the associated dangers).

The next question is, “How does the identity provider return the response to the relying party?” As you might guess, the same redirection mechanism is used again in 4), but this time the identity provider fills out the Location header with the URL of the relying party, and the goop is the identity information required by the RP. As shown in 5), the browser responds to this redirection information by obediently posting back to the relying party.

Note that all of this can occur without the user being aware that anything has happened or having to take any action. For example, the user might have a cookie that identifies her to her identity provider. Then if she is sent through steps 2) to 4), she will likely see nothing but a little flicker in her status bar as different addresses flash by. (This is why I often compare redirection to a world where, when you enter a store to buy something, the sales clerk reaches into your pocket, pulls out your wallet and debits your credit card without you knowing what is going on — trust us…)

Since the identity provider is tasked with telling the browser where to send the response, it MUST know what relying party you are visiting. Because it fabricates the returned identity token, it MUST know all the contents of that token.

So, returning to the axes for linkability that we set up in Evolving Technology for Better Privacy, we see that from an identity point of view, the identity provider “sees all” – without the requirement for any collusion. Knowing each other's identity, the relying party and the identity provider can, in the absence of appropriate policy and suitable auditing, exchange any information they want, either through the redirection channel, or through a “back channel” that dispenses with the user and her browser altogether.

In fact all versions of SAML include an “artifact” binding intended to facilitate this. The intention of this mechanism is that only a “handle” need be exchanged through the browser redirection channel, with the assumption that the IP and RP can then hook up and use the handle to “collaborate” about the user without her participation.

In considering the use cases for which SAML was designed, it is important to remember that redirection was not originally designed to put the “user at the center”, but rather was “intended for cases in which the SAML requester and responder need to communicate using an HTTP user agent… for example, if the communicating parties do not share a direct path of communication.” In other words, an IP/RP collaboration use case.

As Paul Masden reminded us in a recent comment, SAML 2.0 introduced a new element called RelayState that provides another means for synchronizing or exchanging information between the identity provider and the relying party; again, this demonstrates the great amount of trust a user must place in a SAML identity provider.

There are other SAML bindings that vary slightly from the redirect binding described above (for example, there is an HTTP POST binding that gets around the payload size limitations involved with the redirected GET, as Pat Paterson has pointed out). But nothing changes in terms of the big picture. In general, we can say that the redirection protocols promote much greater visibility of the IP on the RPs than was the case with X.509.

I certainly do not see this as all bad. It can be useful in many cases – for example when you would like your financial institution to verify the identity of a commercial site before you release funds to it. But the important point is this: the protocol pattern is only appropriate for a certain set of use cases, reminding us why we need to move towards a multi-technology metasystem.

It is possible to use the same SAML payloads in more privacy-protecting ways by using a different wire protocol and putting more intelligence and control on the client. This is the case for CardSpace in non-auditing mode, and Conor Cahor points out that SAML's Enhanced Client or Proxy (ECP) Profile has similar goals. Privacy is one of the important reasons why evolving towards an “active client” has advantages.

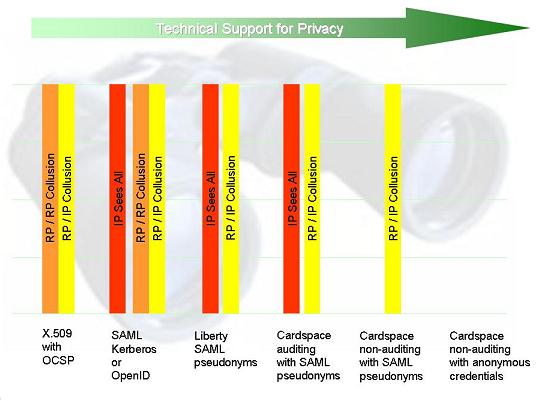

You might ask why, given the greater visibility of IP on RP, I didn't put the redirection protocols at the extreme left of my identity technology privacy spectrum. The reason is that the probability of RP/RP collusion CAN be greatly reduced when compared to X.509 certificates, as I will show next.

What is good about X.509 is that if a relying party does not collude, the CA has no visibility onto the fact that a given user has visited it (we will see that in some other systems such visibility is unavoidable). But a relying party could at any point decide to collude with the CA (assuming the CA actually accepts such information, which may be a breach of policy). This might result in the transfer of information in either direction beyond that contained in the certificate itself.

What is good about X.509 is that if a relying party does not collude, the CA has no visibility onto the fact that a given user has visited it (we will see that in some other systems such visibility is unavoidable). But a relying party could at any point decide to collude with the CA (assuming the CA actually accepts such information, which may be a breach of policy). This might result in the transfer of information in either direction beyond that contained in the certificate itself.