Here's an email I received from John through my I-name account:

I would have left a comment on the appropriate entry in your blog, but you've locked it down and so I can't 🙁

I have a quick question about InfoCards that I've been unable to find a clear answer to (no doubt due to my own lack of comprehension of the mountains of talk on this topic — although I'm not ignorant, I've been a software engineer for 25+ years, with a heavy focus on networking and cryptography), which is all the more pertinent with EquiFax's recent announcement of their own “card”.

The problem is one of trust. None of the corporations in the ICF are ones that I consider trustworthy — and EquiFax perhaps least of all. So my question is — in a world where it's not possible to trust identity providers, how does the InfoCard scheme mitigate my risk in dealing with them? Specifically, the risk that my data will be misused by the providers?

This is the single, biggest issue I have when it comes to the entire field of identity management, and my fear is that if these technologies actually do become implemented in a widespread way, they will become mandatory — much like they are to be able to comment on your blog — and people like me will end up being excluded from participating in the social cyberspace. I am already excluded from shopping at stores such as Safeway because I do not trust them enough to get an affinity card and am unwill to pay the outrageous markup they require if you don't.

So, you can see how InfoCard (and similar schemes) terrify me. Even more than phishers. Please explain why I should not fear!

Thank you for your time.

There's a lot compressed into this note, and I'm not sure I can respond to all of it in one go. Before getting to the substantive points, I want to make it clear that the only reason identityblog.com requires people who leave a comment to use an Information Card is to give them a feeling for one of the technologies I'm writing about. To quote Don Quixote: “The proof of the pudding is the eating.” But now on to the main attraction.

It is obvious, and your reference to the members of the ICF illustrates this, that every individual and organization ultimately decides who or what to trust for any given reason. Wanting to change this would be a non-starter.

It is also obvious that in our society, if someone offers a service, it is their right to establish the terms under which they do so (even requiring identification of various sorts).

Yet to achieve balance with the rights of others, the legal systems of most countries also recognize the need to limit this right. One example would be in making it illegal to violate basic human rights (for example, offering a service in a way that is discriminatory with respect to gender, race, etc).

Information Cards don't change anything in this equation. They replicate what happens today in the physical world. The identity selector is no different than a wallet. The Information Cards are the same as the cards you carry in your wallet. The act of presenting them is no different than the act of presenting a credit card or photo id. The decision of a merchant to require some form of identification is unchanged in the proposed model.

But is it necessary to convey identity in the digital world?

Increasing population and density in the digital world has led to the embodiment of greater material value there – a tendency that will only become stronger. This has attracted more criminal activity and if cyberspace is denied any protective structure, this activity will become disproportionately more pronounced as time goes on. If everything remains as it is, I don't find it very hard to foresee an Internet vulnerable enough to become almost useless.

Many people have come or are coming to the conclusion that these dynamics make it necessary to be able to determine who we are dealing with in the digital realm. I'm one of them.

However, many also jump to the conclusion that if reliable identification is necessary for protection in some contexts, it is necessary in all contexts. I do not follow that reasoning.

Some != All

If the “some == all” thinking predominates, one is left with a future where people need to identify themselves to log onto the Internet, and their identity is automatically made available everywhere they go: ubiquitous identity in all contexts.

I think the threats to the Internet and to society are sufficiently strong that in the absence of an alternate vision and understanding of the relevant pitfalls, this notion of a singular “tracking key” is likely to be widely mandated.

This is as dangerous to the fabric and traditions of our society as the threats it attempts to counter. It is a complete departure from the way things work in the physical world.

For example, we don't need to present identification to walk down the street in the physical world. We don't walk around with our names or religions stenciled on our backs. We show ID when we go to a bank or government office and want to get into our resources. We don't show it when we buy a book. We show a credit card when we make a purchase. My goal is to get to the same point in the digital world.

Information Cards were intended to deliver an alternate vision from that of a singular, ubiquitous identity.

New vision

This new vision is of identity scoped to context, in which there is minimal disclosure of specific attributes necessary to a transaction. I've discussed all of this here.

In this vision, many contexts require ZERO disclosure. That means NO release of identity. In other words, what is released needs to be “proportionate” to specific requirements (I quote the Europeans). It is worth noting that in many countries these requirements are embodied in law and enforced.

Conclusions

So I encourage my reader to see Information Cards in the context of the possible alternate futures of identity on the Internet. I urge him to take seriously the probability that deteriorating conditions on the internet will lead to draconian identity schemes counter to western democratic traditions.

Contrast this dystopia to what is achievable through Information Cards, and the very power of the idea that identity is contextual. This itself can be the basis of many legal and social protections not otherwise possible.

It may very well be that legislation will be required to ensure identity providers treat our information with sufficient care, providing individuals with adequate control and respecting the requirements of minimal disclosure. I hope our blogosphere discussion can advance to the point where we talk more concretely about the kind of policy framework required to accompany the technology we are building.

But the very basis of all these protections, and of the very possibility of providing protections in the first place, depends on gaining commitment to minimal disclosure and contextual identity as a fundamental alternative to far more nefarious alternatives – be they pirate-dominated chaos or draconian over-identification. I hope we'll reach a point where no one thinks about these matters absent the specter of such alternatives.

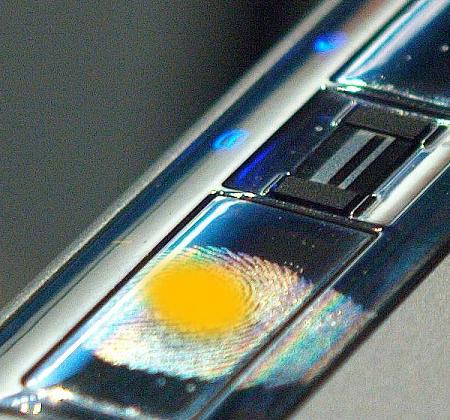

Finally, in terms of the technology itself, we need to move towards the cryptographic systems developed by David Chaum, Stefan Brands and Jan Camenisch (zero knowledge proofs). Information Cards are an indispensible component required to make this possible. I'll also be discussing progress in this area more as we go forward.