Joerg Resch at Kuppinger Cole points us to new research showing how social networks can be used in conjunction with browser leakage to provide accurate identification of users who think they are browsing anonymously.

Joerg writes:

Thorsten Holz, Gilbert Wondracek, Engin Kirda and Christopher Kruegel from Isec Laboratory for IT Security found a simple and very effective way to identify a person behind a website visitor without asking for any kind of authentication. Identify in this case means: full name, adress, phone numbers and so on. What they do, is just exploiting the browser history to find out, which social networks the user is a member of and to which groups he or she has subscribed within that social network.

The Practical Attack to De-Anonymize Social Network Users begins with what is known as “history stealing”.

Browsers don’t allow web sites to access the user’s “history” of visited sites. But we all know that browsers render sites we have visited in a different color than sites we have not. This is available programmatically through javascript by examining the a:visited style. So malicious sites can play a list of URLs and examine the a:visited style to determine if they have been visited, and can do this without the user being aware of it.

This attack has been known for some time, but what is novel is its use. The authors claim the groups in all major social networks are represented through URLs, so history stealing can be translated into “group membership stealing”. This brings us to the core of this new work. The authors have developed a model for the identification characteristics of group memberships – a model that will outlast this particular attack, as dramatic as it is.

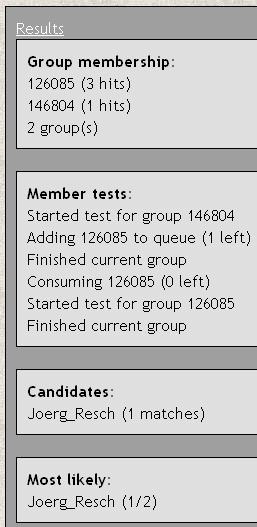

The researchers have created a demonstration site that works with the European social network Xing. Joerg tried it out and, as you can see from the table at left, it identified him uniquely – although he had done nothing to authenticate himself. He says,

“Here is a screenshot from the self-test I did with the de-anonymizer described in my last post. I´m a member in 5 groups at Xing, but only active in just 2 of them. This is already enough to successfully de-anonymize me, at least if I use the Google Chrome Browser. Using Microsoft Internet Explorer did not lead to a result, as the default security settings (I use them in both browsers) seem to be stronger. That´s weird!”

Since I’m not a user of Xing I can’t explore this first hand.

Joerg goes on to ask if history-stealing is a crime? If it’s not, how mainstream is this kind of analysis going to become? What is the right legal framework for considering these issues? One thing for sure: this kind of demonstration, as it becomes widely understood, risks profoundly changing the way people look at the Internet.

To return to the idea of minimal disclosure for the browser, why do sites we visit need to be able to read the a:visited attribute? This should again be thought of as “fingerprinting”, and before a site is able to retrieve the fingerprint, the user must be made aware that it opens the possibility of being uniquely identified without authentication.