The MedPage Today blog recently wrote about “iPhone Security Risks and How to Protect Your Data — A Must-Read for Medical Professionals.” The story begins:

Many healthcare providers feel comfortable with the iPhone because of its fluid operating system, and the extra functionality it offers, in the form of games and a variety of other apps. This added functionality is missing with more enterprise-based smart phones, such as the Blackberry platform. However, this added functionality comes with a price, and exposes the iPhone to security risks.

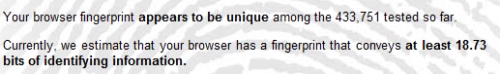

Nicolas Seriot, a researcher from the Swiss University of Applied Sciences, has found some alarming design flaws in the iPhone operating system that allow rogue apps to access sensitive information on your phone.

MedPage quotes a CNET article where Elinor Mills reports:

Lax security screening at Apple's App Store and a design flaw are putting iPhone users at risk of downloading malicious applications that could steal data and spy on them, a Swiss researcher warns.

Apple's iPhone app review process is inadequate to stop malicious apps from getting distributed to millions of users, according to Nicolas Seriot, a software engineer and scientific collaborator at the Swiss University of Applied Sciences (HEIG-VD). Once they are downloaded, iPhone apps have unfettered access to a wide range of privacy-invasive information about the user's device, location, activities, interests, and friends, he said in an interview Tuesday…

In addition, a sandboxing technique limits access to other applications’ data but leaves exposed data in the iPhone file system, including some personal information, he said.

To make his point, Seriot has created open-source proof-of-concept spyware dubbed “SpyPhone” that can access the 20 most recent Safari searches, YouTube history, and e-mail account parameters like username, e-mail address, host, and login, as well as detailed information on the phone itself that can be used to track users, even when they change devices.

Following the link to Seriot's paper, called iPhone Privacy, here is the abstract:

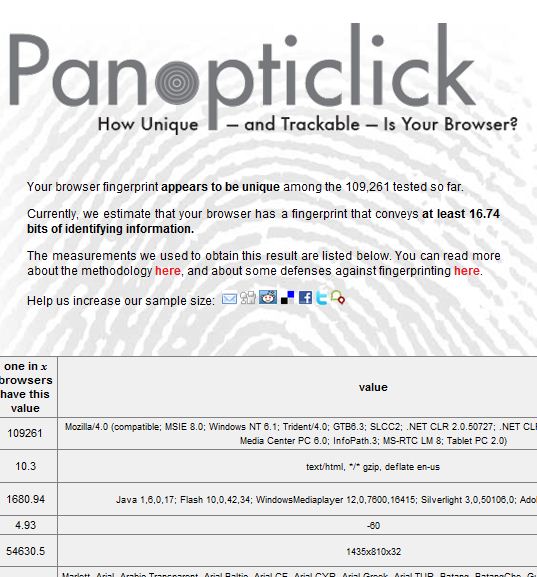

It is a little known fact that, despite Apple's claims, any applications downloaded from the App Store to a standard iPhone can access a significant quantity of personal data.

This paper explains what data are at risk and how to get them programmatically without the user's knowledge. These data include the phone number, email accounts settings (except passwords), keyboard cache entries, Safari searches and the most recent GPS location.

This paper shows how malicious applications could pass the mandatory App Store review unnoticed and harvest data through officially sanctioned Apple APIs. Some attack scenarios and recommendations are also presented.

In light of Seriot's paper, MedPage concludes:

These security risks are substantial for everyday users, but become heightened if your phone contains sensitive data, in the form of patient information, and when your phone is used for patient care. Over at iMedicalApps.com, we are not fans of medical apps that enable you to input patient data, and there are several out there. But we also have peers who have patient contact information stored on their phones, patient information in their calendars, or are accessible to their patients via e-mail. You can even e-prescribe using your iPhone.

I don't want to even think about e-prescribing using an iPhone right now, thank you.

Anyone who knows anything about security has known all along that the iPhone – like all devices – is vulnerable to some set of attacks. For them, iPhone Privacy will be surprising not because it reveals possible attacks, but because of how amazingly elementary they are (the paper is a must-read from this point of view).

On a positive note, the paper might awaken some of those sent into a deep sleep by proselytizers convinced that Apple's App Store censorship program is reasonable because it protects them from rogue applications.

Evidently Apple's App Store staff take their mandate to protect us from people like award winning Mad Magazine cartoonist Tom Richmond pretty seriously (see Apple bans Nancy Pelosi bobble head). If their approach to “protecting” the underlying platform has any merit at all, perhaps a few of them could be reassigned to work part time on preventing trivial and obvious hacker exploits..

But I don't personally think a closed platform with a censorship board is either the right approach or one that can possibly work as attackers get more serious (in fact computer science has long known that this approach is baloney). The real answer will lie in hard, unfashionable and (dare I say it?) expensive R&D into application isolation and related technologies. I hope this will be an outcome: first, for the sake of building a secure infrastructure; second, because one of my phones is an iPhone and I like to explore downloaded applications too.

[Heads Up: Khaja Ahmed]

It could be years or even decades before the divorce was finally approved. Today, it only takes 15 minutes for a couple to go through the formalities to tie or untie the knot at local civil affair bureaus.

It could be years or even decades before the divorce was finally approved. Today, it only takes 15 minutes for a couple to go through the formalities to tie or untie the knot at local civil affair bureaus.