A lot of people have asked me, “But how does a user GET a managed Information Card?” They are referring, if you are new to this discussion, to obtaining the digital equivalent to the cards in your wallet.

I sometimes hum and ha because there are so many ways you can potentially design this user experience. I explain that technically, the user could just click a button on a web page, for example, to download and install a card. She might need to enter a one-time password to make sure the card ended up in the hands of the right person. And so on.

But now that production web sites are being built that accept InfoCards, we should be able to stop arm-waving and study actual screen shots to see what works best. We'll be able to contrast and compare real user experiences.

Vittorio Bertocci, a colleague who blogs at vibro.net, is one of the people who has thought about this problem a lot. He has worked with the giant European Etailer, Otto, on a really slick and powerful smart client that solves the problem. Otto and Vittorio are really on top of their technology. It's just a day or two after Vista and they have already deployed their first CardSpace application – using branded Otto cards.

Here's what they've come up with. I know there are a whole bunch of screen shots, but bear in mind that this is a “registration” process that only occurs once. I'll hand it over to Vittorio…

The Otto Store is a smartclient which enables users to browse and experience in a rich way a view of Otto's products catalog. Those functions are available to everyone who downloads and installs the application (it is in German only, but it is very intuitive and a true pleasure for the eye). The client also allows purchase of products directly from the application: this function, however, is available only for Otto customers. For being able to buy, you need to be registered with http://www.otto.de/.

That said: while buying on http://www.otto.de/ implies using username and password, the new smart client uses Otto managed cards. The client offers a seamless provisioning experience, thanks to which Otto customers can obtain and associate to their account an Otto managed card backed by a self issued card of their choice.

Let's get a closer look through the screens sequence.

Above you see the main screen of the application. You can play with it, I'll leave the sequence for adding items in the shopping cart to your playful explorations (hint: once you're chosen what to buy, you can reach the shopping cart area via the icon on the right end.

Above you see the shopping cart screen. You can check out by pressing the button circled in red.

Now we start talking business! On the left you are offered the chance of transfering the shopping cart to the otto.de web store, where you can finalize the purchase in “traditional” way. If you click the circled button on the right, though, you will be able to do go on with the purchase without leaving the smartclient and securing the whole thing via CardSpace. We click this button.

This screen asks you if you already own an Otto card or if you need to get one. I know what you are thinking: can't the app figure that out on its own? The answer is a resounding NO. The card collection is off limit for everybody but the interactive user: the application HAS to ask. Anyway, we don't have one Otto card yet so the question is immaterial. Let's go ahead and get one. We click on the circled button on the left.

This screen explains to the (German-speaking) user what is CardSpace. It also explains what is going to happen in the provisioning process: the user will choose one of his/her personal card, and the client will give back a newly created Otto managed card. We go ahead by clicking the circled button.

Well, that's end of line for non-Otto customers. This screen allows the user to 1) insert credentials (customer number and birthdate) to prove that they are Otto customers and 2) protect the message containing the above information with a self issued card. This is naturally obtained via my beloved WS-Security and seamless WCF-CardSpace integration. Inserting the credentials and pushing the button in the red circle will start the CardSpace experience:

The first thing you get is the “trust dialog” (I think it has a proper name, but I can't recall it right now). Here you can see that Otto has a Verisign EV certificate, which is great. I definitely believe it deserves my trust, so I'm going ahead and chosing to send my card.

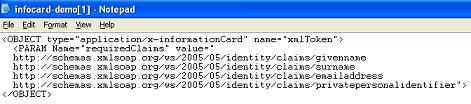

Here there's my usual card collection. I'm going to send my “Main Card”: let's see which claims the service requires by clicking “Preview”.

Above you can see details about my self issued card. Specifically, we see that the only claim requested is the PPID. That makes sense: the self issued card will be used for generating the Otto managed card so the PPID comes in handy. Furthermore, it makes sense that no demographic info are requested: those have been acquired already, through a different channel. What we are being requested is almost a bare token, the seond authentication factor that will support our use of our future Otto managed card. Let's click “Send” and perform our ws-secure call.

The call was successful: the credentials were recognized, the token associated to self issued card parsed: as a result, the server generated my very own managed card and sent it back to you. Here's there is something to think about: since this is a rich client application, we can give to the user a seamless provisioning experience. I clicked “Send” in the former step, and I find myself in the Import screen without any intermediate step. How? The bits of the managed card (the famous .CRD file) are sent as a result of the WS call: then the rich client can “launch” it, opening the cardspace import experience (remember, there are NO APIs for accessing the card store: everything must be explicitly decided by the interactive user). What really happens is that the cardspace experience closes (when you hit send) and reopens (when they client receives the new card) without any actions required in the middle. If the same process would have happened in a browser application, this would not be achievable. If the card is generated in a web page, the card bits will probably be supplied as a link to a CRD card: when the user follows the link, it will be prompted by the browser for choosing if he/she wants to save the file or open it. It's a simple choice, but it's still a choice.

Back on the matter at hand: I'm all proud with my brand new Otto card, and I certainly click on “Install” without further ado. The screen changes to a view of my card collection, which I will spare you here, with its new citizen. You can close it and get back to the application.

The application senses that we successfully imported the managed card (another thing that would be harder with web applications). The provisioning phase is over, we won;t have to go through this again when we'll come back to the store in the future.

At this point we can click on the circled button and give to our new Otto Card a test drive: that will finally secure the call that will start the checkout process.

Here's we have my new card collection: as expected, the Otto card is the only card I can use here. Let's preview it:

Here's the set of claims in the Otto card: I have no hard time to admit that apart from “Strasse” and “Kundennummer” I have no idea of what those names mean :).

I may click on “Retrieve” and get the values, but at the time of writing there's no display token support yet: nothing to be worried about in term of functionality, you still get the token that will be used for securing the call: click the circled button for making the token available to WCF for securing the call.

Please note: if you are behind a firewall you may experience some difficulties a this point. If you have problems retrieving the token, try the application from home and that should fix it.

That's it! We used our Otto managed card, the backend recognized us and opened the session: from this moment on we can proceed as usual. Please note that we just authenticated, we didn't make any form of payment yet: the necessary information about that will be gathered in the next steps.

Also note that it was enough to choose the Otto managed card for performing the call, we weren't prompted for further authentication: that is because we backed the Otto card with a personal card that is not password protected. The identity selector was able to use the associated personal card directly, but if it would have been password protected the selector would have prompted the user to enter it before using the managed card.It definitely takes longer to explain it than to make it. In fact, the experience is incredibly smooth (including the card provisioning!).

Kim, here's some energy for fueling the Identity Big Bang. How about that? 🙂

That's great, Vittorio. I hear it.

By the way, Vittorio is a really open person so if you have questions or ideas, contact him.